One desires a grand setting for grand occasions, so it’s a bit deflating to recall that the makeup of my inner life was profoundly reordered on a day I likely hadn’t showered, nor slept well, and probably missed breakfast.

On the day I first encountered Carol Ann Duffy’s poems, I was a twenty-six-year-old student at California State University, Long Beach, nearing the end of a comically protracted undergraduate career. I had spent six years in a community college, seemingly intent on reading everything except the work assigned by professors, until I finally cobbled together enough credits to transfer to a local state school. And that’s where I was, doodling in the margins of my notebook, when my professor began reciting a poem from memory, one that made me set down my pen and listen. The poem was Duffy’s “Mrs Lazarus,” a retelling of the Biblical story where Jesus raises a man from the dead.

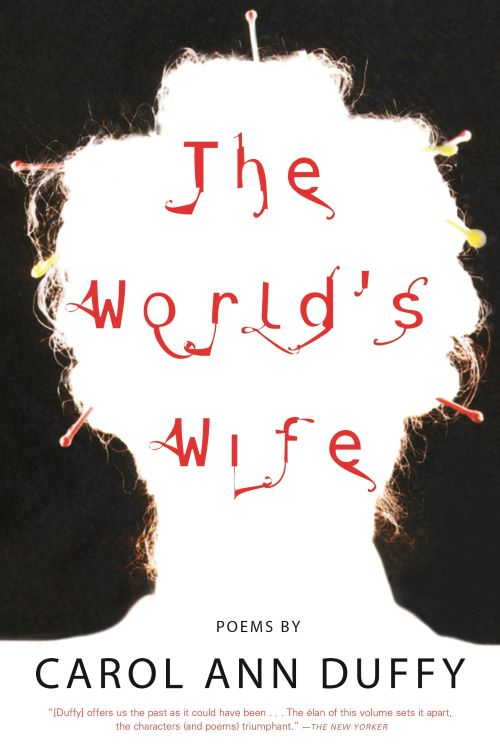

Now, I like to pretend that I first encountered her work on a gray day, brewing endless, needless cups of tea under a leaden English sky, reading by the fireplace. The experience of her poems seems to require that kind of monumentality. In a way, though, the mundanity of the real story gets at the heart of The World’s Wife: throughout the book, our meticulous cultural inheritance—our gods, our legends, our myths, our grandest stories—are stripped of their sheen and recast on a smaller, human scale. The collection is comprised of a series of dramatic monologues from the perspectives of the women who have been sidelined, overlooked, omitted: Pilate’s wife, Mrs Midas, Frau Freud, Little Red Riding Hood, Medusa, Queen Herod. Sometimes they are cheeky, sometimes enraged. Duffy includes anachronistic details—Mrs Midas parking a car, Mrs Lazarus knotting a tie—and gives each woman a casual, everyday linguistic register. The result is—dare I say the word—an accessible collection of poems whose form invites you into the Western Canon through a side door, so to speak. She retells these great and complicated works while taking them down a peg or two.

Duffy’s un-stuffiness and accessibility appealed to a self-styled autodidact like me, who’d found higher education somewhat myopic and stifling. That said, as I began to read more attentively, I started to notice her sly virtuosity, like the twenty-five different end rhymes she finds for the word jerk in “Mrs Sisyphus,” or the brilliant metaphorical images she achieves again and again in the collection.

This approach—Duffy’s dual reverence for the Western Canon and her simultaneous roasting of it (for all those it omits)—has stayed with me in a profound way since that morning in Long Beach so long ago, and not just in books but in other facets of life. Even now, when I walk through an art museum, say, I will imagine the essential figures who aren’t there, who never made it onto the canvas, who, to crib a line from Duffy, were disinherited out of their time.