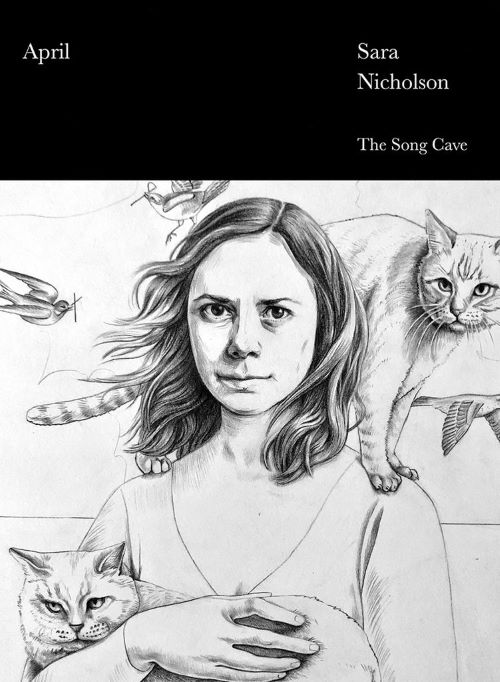

Chaucer inaugurated Middle English poetry by invoking “Aprille, with his shoures soote.” We could say that Eliot did the same for poetic modernism when he declared that “April is the cruellest month.” From that vantage, it’s a bold thing to title a book of poems April, as Sara Nicholson has done.

Both of these earlier Aprils signify rebirth. They are also both, in their own ways, about desire, its rekindling after a long winter’s sleep. For Chaucer, April brings with it the longing to “goon on pilgrimage.” Eliot, for his part, despairs at desire’s return, at the “breeding,” “mixing,” and “stirring” of reawakened desire, which he knows will end in pain.

What does Nicholson’s April have to say to, or about, Eliot’s “April,” Chaucer’s “Aprille”? The title poem begins:

It can be nice, some days

To sit down and think.

Fresh air is good.

Matter in variety is good

For the body.

A little pepper on the biscuit, not

Too much onion, just a slice.

In what sort of April do we find ourselves here? It is quiet, pleasant (from another poem, “Everyone’s Poem,” in which the word “April” also appears: “Life is pleasant. Paradise too / Dry or wet”). Our needs are met, or aren’t hard to meet. The world has long been disenchanted; Chaucer’s “Zephyrus” has left us, although the wind still blows, “If only just.” There are no gods, but much is good:

The wind is good

And so am I

Bored with desiring, exchanging ticket

For ticket, sail for sail.

The snow is good

And the rain.

It is April, and we are once again confronted with desire. But now we’ve arrived at desire’s end: not the exhaustion of desire, which leads only to further desire, but to boredom with desire—in other words, transcendence. We’ve arrived at the April of the present (from another poem, “A Crown for Iris”: “I don’t believe in God and yet I do / believe in ∞, the power / Of the present tense”), looking to neither the future nor the past. Here we are, in the April to end all Aprils, with a biscuit, the snow, the wind, and the rain.

The little litany above is emblematic of one of April’s many charms, which is its treatment of nature as coextensive with art. “Natural” objects appear most often in these poems as they do in the title poem, as simple nouns with the heft of medieval allegorical figures—as if they ought to be, or could be, capitalized: the Snow, the Wind, the Rain. As if Nature were already Art before being incorporated into it.

The title of the poem I’ve featured states this plainly: “Nature Is Art.” Is Nature really Art? (Is Truth really Beauty?). April makes its case by way of demonstration, whether through ekphrasis (see “The Archetype” and “The Goatherd and the Saint”) or through its insistence on describing the world with an artist’s eye, as if the world were made of paint, or pixels, or ink: “I absent myself from fate / A little too often, snowdrops / Spring up on us yet again / In colors dripped on the grass / Which is dead.”

Poetry, it goes without saying, is also Art, and therefore also Nature. April makes the case for this, too: “I would begin to sing it / For you, I’d tell the story / End-stopped by snow, the poem / Of a world without pain.” Near the end of the book, in the prose series “Lives of the Saints,” Nicholson writes that she wants:

…to read poems the way monks read scripture, to practice what is called lectio divina (“divine reading”). It’s a slow process, like building a fire with wet wood. It requires focus of a radically laborious kind.

Maybe what Nature and Art have in common is their amenability to being read—the fact that both can be the object of lectio divina, the contemplation of the “living word.” In April the gods have left us, but Nature, like poetry, is being written, and can be read. The world is a poem, or a painting, and a poem, in turn, is the world, or at least a world (an “imaginary garden[] with real toads in [it],” if you will). In that sense, April seems to argue, to count stresses is to “tally stars,” to “tell the story / End-stopped by snow”; it is a way of arranging the “Leaves drying on the blacktop / Loosely iambic, wet with ash.” In a poem it is always April, month of rebirth. And in the infinite April of the present tense, Nature is Art, Art Nature. The living word is the living world.