Around the holidays in 2019, I saw the PBS docuseries College Behind Bars, a four-episode look at incarcerated scholars participating in the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), a rigorous philanthropically funded prison education program in which students study full-time and complete associate and bachelor’s degree programs. The following spring, I shared it with my classes at Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA), and students discussed featured scholars—Sebastian, who uses his graduation speech to apologize to his father in Korean (a language many of my students understood); Giovannie, who studies the intersection of poetry and art by tackling texts like The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara and criticism by Charles Altieri; and Dyjuan, who leads the Bard debate team to a win against Harvard.

When I prepared materials for the Fairfax Poet Laureate application a few months later, I envisioned a tenure project that offered reading and writing workshops to high school students including those in the county’s juvenile detention center (JDC) in large part because of the enthusiasm for learning demonstrated by those BPI scholars. A few months later in March 2020, Linda Sullivan, CEO of ArtsFairfax, called to confirm my appointment. While the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the start of the program and narrowed its scope to the JDC, the residency was an example of how community-facing programs can meet poetry readers and writers where they are, amplify their stories, validate their experiences, and offer these scholars strategies for processing periods of transition and uncertainty.

As a child, I spent time in shelters for women and children, and because they were difficult periods, the occasions to laugh, craft, and create were particularly meaningful. While living in a shelter, I learned to make pompoms for roller skates by winding yarn around two cardboard doughnuts, slicing between them, and securing the fragments down a medial line; it hardly mattered my roller skates were a thousand miles away with the rest of my possessions. Around the 4th of July, a volunteer helped us create a full-page mosaic with colored pencil before convincing us to cover the pattern with a black crayon imitating the night sky. She guided us in using scissors to replicate the shape of fireworks, carving into the darkness to reveal what hid underneath. These occasions to create kept me afloat, so it was no surprise that when I found myself at the door of a shelter the summer after my freshman year at Davidson College, it was reading and writing poems that helped me navigate the sense of betweenness I felt—being a student at an institution of great prominence while temporarily relying on the resources of a shelter.

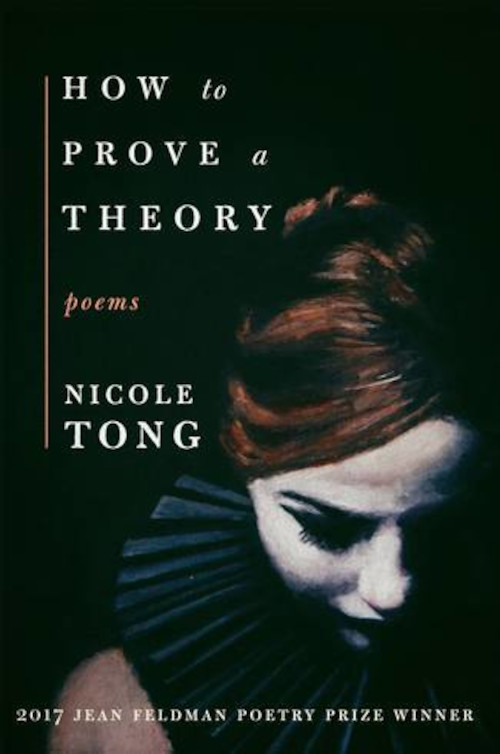

It was May 1999. I took a duffle bag of clothes and a few books including The Gatehouse Heaven by James Kimbrell, which I’d read for the first time in Dr. Gill Holland’s English class the previous autumn. In its titular poem, the speaker asks, “And what did I know of madness or fathers?” I felt a connection with the question, the poet who could raise it, and the poem’s personification of silence. The book opened a door of possibility; though I was the most isolated I had ever been, I was not alone. I called my Fairfax Poet Laureate tenure project “Poetry Lives Here”—a way of acknowledging the literary happenings in our county in addition to the pedagogical philosophy of reading living authors in the JDC residency, which is also the hallmark of the college classes I teach. I aim to assign or recommend books that help others “find their people” in living writers in their own periods of transition or uncertainty.

The residency required a shared commitment to the success of the scholars with an emphasis on literacy—reading books in-full and writing poems inspired by those books. Before the end of 2021, ArtsFairfax Education Manager Hope Cagle and I offered a program plan with several components:

a. Participation of the BETA program (male) scholars and female scholar(s) with agendas, texts, and weekly poetry prompts for each group

b. Mentorship between George Mason University MFA students and JDC scholars

c. A pedagogy of living poets to include full collection reading, single poem mentor texts and poetry prompts

d. Collaboration between the Fairfax Poet Laureate, JDC teachers and principal, ArtsFairfax, George Mason University’s MFA director, and Poetry Daily

e. Cultural capital-building (through conversations about higher education and life after the JDC)

Before we began our work, JDC Principal Eric Shaver offered tours to all stakeholders. We saw the scholars’ classrooms and a full library with class sets of books in multiple languages, and we met the “counselors” who would ensure the safety of our in-person sessions. Shaver explained the importance of “traveling light”—bringing into the sessions only what we absolutely needed. Something as small as a missing pen would be grounds to suspend activity across the entire facility until it was found. We learned more about the BETA cohort and the wrap-around behavioral, mental health, and substance abuse treatment many receive in addition to their academics. Finally, we planned our bi-monthly sessions in consultation with their language arts teacher and literacy coach. Using Google drive, I offered agendas and prompts in advance, and Hope Cagle provided each participant with a journal and the texts. Shaver told us the books would be, for some participants, the first they would call their own and assured us that when the scholars left the JDC, those books would leave with them. While Principal Shaver was happy for students to have special access to the resources of the program, he was particularly excited to leverage my role as a community college professor at NOVA to boost students’ confidence. When he introduced our work to students he said, “Ms. Tong is not going to go easy on you. She is used to teaching college.”

Teach Living Poets (NCTE, 2021), by co-authors Melissa Alter Smith and Lindsey Illich, was a guiding light for the JDC program. For the BETA men, I selected Clint Smith’s Counting Descent (Write Bloody, 2016) and José Olivarez’s Citizen Illegal (Haymarket, 2018). Not only were they collections I had taught before, but they are collections for which there are thoughtful ready-to-use resources thanks to educators like Melissa Smith (#TeachLivingPoets founder), Joel Garza, and Scott Bayer (#TheBookChat cofounders) who lead Twitter conversations about using contemporary poetry effectively in the classroom. For the women, I discovered Diana Whitney’s gorgeous anthology, you don’t have to be everything (Workman, 2021), which is organized around feelings such as longing, shame, and belonging.

Each week, I added 3-5 prompts inspired by the lesson of the session to scholars’ journals for them to complete as they wished in the week we did not meet. We spent the first half of our 90 minutes together reading and asking critical questions of the texts and the second half writing and sharing. After we met with the BETA cohort, this process repeated for the women. George Mason University MFA poetry mentors, Hope Cagle of ArtsFairfax, and I shared our in-session writing alongside the JDC scholars who volunteered. JDC Counselors and Principal Shaver sat in and even participated as they could. Their consistent buy-in meant that while the scholars may have been reticent to write poems at first, we created community quickly. Conversations about verb clauses, enjambment, and anaphora were peppered with one-on-one stories about a student’s experiences prior to the JDC. On occasion, we would have a breakthrough—the extent of which we could not appreciate on our own until the scholars’ teachers shared what was remarkable about a detail in a poem. For example, after one prompt, one of the BETA scholars shared a poem, a hopeful letter to a child a woman in his life was expecting though he had trouble talking about those feelings outside of a workshop context.

While sessions began on Zoom due to COVID protocols, in the months that followed, our visits moved to in-person events. Scholars created erasure poems, elegies, and odes; some of the more memorable scholar poems came about following mentor texts including Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s “Miss you. Would like to take a walk with you,” which students used as a catalyst to share what or who they missed about life before the JDC. Leila Chatti’s “Cootie Catcher” offered us a way to use poems, colors, and emotions in a poem alongside a grammatical discussion of noun and verb phrases. Students used their mentor-partner to help them craft ‘kinetic’ poem stanzas layered upon each other and recorded those pieces in their journals.

In our penultimate meeting, JDC women were joined by Diana Whitney, and BETA program men were able to meet José Olivarez. While this was a surprise for students, asking poets whose work scholars had studied was the blue skies scenario I shared with Poetry Daily Executive Co-Editor Peter Streckfus in a late summer conversation as one possible benchmark for the program’s success. Nearly a year later, both poets generously agreed to join our workshop via Zoom. Fairfax County’s Channel 16 news even captured the occasion for its County Magazine June 2022 feature. Olivarez and Whitney read their favorite selections and answered questions about life as professional writers and editors. Both honorary guests got to hear the scholars’ poems their books inspired and selections within those texts that most resonated with workshop participants. Scholars shared the ways the books changed their minds about poetry and experienced the kind of meaningful connection that bridges a poem on the page and a person in the world who, in Olivarez’s words, was “rooting for them.”

Two weeks later, we marked the end of the residency with celebratory breakfast tacos, erasure poems, a PBS video clip offering a poetic origin story of Freedom Reads Founder Reginald Dwayne Betts in his interview with Jeffrey Brown. In it, Brown describes a crime that took place in the county where the many of the JDC scholars were raised. As the scholars watched, they used a thick black marker to find the poetry within a page of prose. I circulated Felon to show them the poet’s work, a large-scale version of the erasure prompt they were completing. In the clip, Betts says, “Poetry was my idea of how to be somebody.” They heard about his path after prison—from community college to Yale Law School to a special appointment on a White House commission on juvenile justice.

After the clip, students were invited to ask big questions about college to someone with whom the scholars could relate—a NOVA community college student around their same age who had been appointed by Virginia Poet Laureate Dr. Luisa Igloria as one of five college-level Young Poets in the Community. Of her, scholars asked what college was like, how she came up with her major, and whether she had a minor path of study. Our visitor shared poems of her and spoke about the relationships with mentors that helped her thrive. While the program’s final session took place in May 2022, in June of that month Hope Cagle of ArtsFairfax was a guest at the high school graduation of a BETA scholar. No longer a member of the BETA cohort, he began a residential bachlor’s degree program this fall.

Programs like “Poetry Lives Here” are the result of a series of yeses and a village invested in a common goal, group, and ethos. Poetry by living poets reminds us that we live in a world shared by others in real time, and that especially matters during liminal periods marked by uncertainty and isolation. I’m inspired by people—JDC scholars, my community college students, women and children living in shelters— who navigate these waters—however they can—and (to borrow from the great Lucille Clifton) manage to “sail through this to that”.