The first time I heard Tarfia Faizullah read “Self-Portrait as Mango” was in a barn in Vermont in 2014. It was at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and all week I had been immersed in words and craft talks. And then I heard Tarfia read. For me, the word exotic has been a word loaded with meaning since I was a child. My mother’s accent was exotic. The smell of our food cooking was exotic. Don’t you look exotic! was exclaimed whenever I was in a salwar kameez or sari. Even our names were declared exotic. The feelings around the word were complicated for me, and I had written a short story about the very word. And still felt I hadn’t said what I wanted to say. And then I heard “Self-Portrait as Mango”.

The self-portrait poem is a form that has been considered by numerous poets from John Ashbery to Frank Bidart. Walt Whitman said, “I celebrate myself, and sing myself.” If a portrait is a means of capturing a likeness, self-portrait poems give the reader a way to not only encounter the other, but to also see poems as an exploration of self.

We live in a moment where capturing ourselves is a phenomenon. We do this in selfies, and every day through Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook — we offer a version of ourselves. Self-portrait poems perhaps are the original selfie — in words we offer the reader a translation of ourselves, one that may be distorted or incredibly real.

“Self-Portrait as Mango” is a kind of ghazal — the traditional Arabic verse form. Persian poets adopted the form, and the late poet Agha Shahid Ali advanced the form to many in the West. A ghazal is usually between five and fifteen discrete couplets. The form has a sophisticated rhyme scheme where usually the couplets end with the same word or phrase — and a rhyming word usually comes before the refrain. Generally, each couplet is the same in meter and length.

Faizullah subverts the ghazal to get her point across — she is not interested in rhyme per se, but instead repetition. The reiteration of the word mango again and again drives home her tone and anger:

I say, Suck on a mango, bitch, since that’s all you think I eat anyway. Mangoes

are what margins like me know everything about, right? Doesn’t

a mango just win spelling bees and kiss white boys?”

And later in the poem:

won’t be cracked open to reveal whiteness to you. This mango

isn’t alien just because of its gold-green bloodline. I know

I’m worth waiting for. I want to be kneaded for ripeness.”

Those lines. Not being cracked up to reveal whiteness. Her tone is indignant but controlled. She is commanding the narrative of the stereotypes that surround otherness with a deft and clear hand.

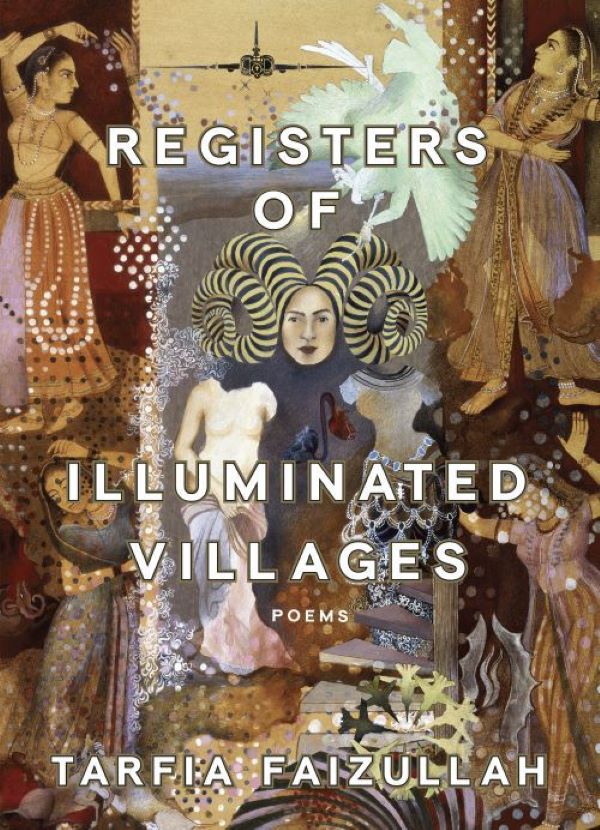

The poem was later published in the collection Registers of Illuminated Villages: Poems — and the whole stunning book explores ancestry, trauma, and grief. Each poem is taut in its meaning and language.

Faizullah to me is a poet that speaks to in-betweenness and to the myths of model minorities. That night in Vermont, I felt electric when I heard the poem. Her anger was something I had been scared to ever utter. She put into words what so many of us felt. It wasn’t just a portrait of herself, it was a portrait of us all.