THE EYE OF THE RAINBOW

When I first read the kaleidoscopic poem “Arcobaleno” (“Rainbow”), I had been studying and translating the poetry of war for decades. Rarely did I encounter poems about rainbows in those days. I also knew nothing about the author, Ardengo Soffici. But I was thoroughly intrigued by the colorful, surreal landscape of the poem, full of sensory stimuli from unlikely sources: the voice of the moon, the fragrance of nights drowned in topaz armpits, the sight of the Seine as a garden of blazing flags, the feeling of hands stained with the liquors of sunset.

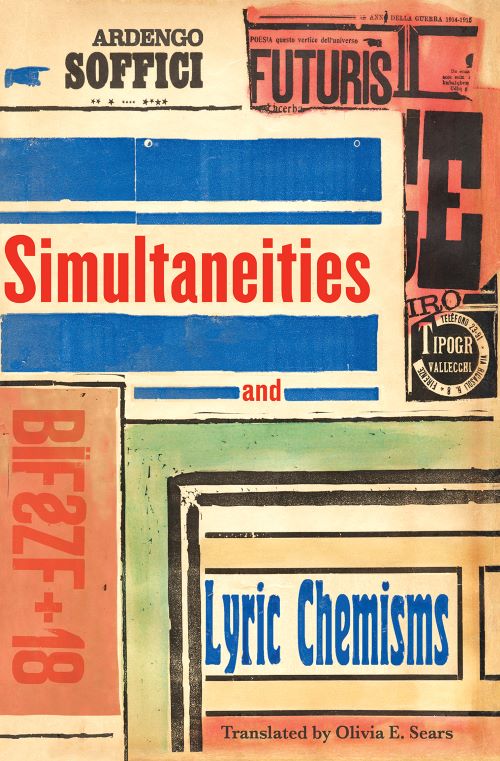

I tracked down the book, Simultaneità e chimismi lirici, and discovered a 1915 volume of poetry dedicated to a radical renewal of art and culture in what Soffici termed an Italia dormiente (dormant Italy). Soffici’s approach to renewal was quite different from that of his Futurist contemporaries in the Italian avanguardia. Unlike other writers, Soffici came to the project as a painter and art critic steeped in the contemporary art of France, where he spent much of the prior decade working among the most influential Impressionist and Cubist painters (Picasso, Matisse, Cezanne, and so on)—along with visual poets like Apollinaire—and introducing their work to Italy. He was trained in the power of the eye.

“Rainbow” performs a demonstration of Soffici’s manifesto for renewal, both urging the artist to wake up, revive, and take their place at the center of things, like a wizard or an alchemist, and doing so himself with the poem. Poets, like painters, he shows us, would need new techniques to respond to this radically new century. But rather than the aggressive techniques the Futurists advocated—the violent imagery and bombastic declarations designed to wrench Italy into the new century by force—Soffici chose color and expressive typography to reproduce the vibrancy, disorientation, and sensory overload of early twentieth-century life.

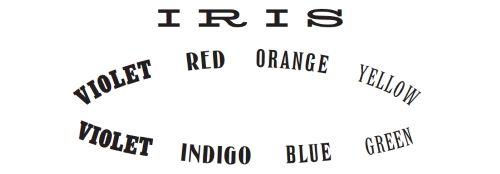

Central to his project is the “eye” of the artist, which is inextricably linked with the rainbow. The spectrum of colors is central both to sight and to painting, of course, but in Italian the eye and the rainbow are also linked linguistically. Throughout the book, Soffici alternates between two different words for rainbow: “arcobaleno” (rainbow) and “iride,” which can also refer to the iris (both botanical and anatomical). Soffici plays with this ambiguity in a later poem where he turns his gaze to a simple glass of water and enters a “pyrotechnical sphere of fantasy” where the word IRIDE (iris / rainbow) floats above an eye constructed with rainbow color names:

The eye of the rainbow. Almost every poem in the book features a panoply of swirling colors or a rainbow or both. While his Futurist contemporaries glorified struggle, Soffici wrote of color and sight.

* * *

Soffici opens “Rainbow” by declaring the date: it is the day after his birthday, in early April 1915. The poem appeared in his magazine Lacerba, a month later (May 8), on the eve of Italy’s entry into World War I (May 23). It was one of the final poems Soffici wrote before his own departure for the front.

In the spring of 1915, Soffici was strongly advocating for Italy to enter the war, and he would volunteer to fight as soon as he could. And yet, on the eve of the war, he did not write a call to arms, but a call to the artist to rise up, to “look around / and write as you dream / to revive the face of our joy.” No call for “regenerative violence,” no sanctified machines of war, no annihilation, as demanded by the Futurists, particularly as the war loomed.

It was striking to me that Soffici wrote this poem full of beauty and tenderness, while he was (simultaneously) preparing for war. After all, the rainbow is also associated with hope, what lies beyond our sight, at the other end of the arc. Soffici had written years before about existential dread and about his efforts to combat the void: “Art for me is the only way to escape the concept of nothingness that otherwise haunts and terrifies me.” In these poems, he filled that void with color, shape, sound, and alchemical transformation.

Sadly, Italy’s entry into war immediately killed the Florentine avant-garde and its ideals; there was no cultural renewal, and Soffici would return from the war “a changed man,” in his words. He denounced his prewar experimental work. Years later, in the face of the 1915 book’s popularity, he would republish the poems, but reworked in a new form dedicated to “order,” with punctuation introduced (to excess) and the concrete poems reduced to lines of text. The wild, colorful experiment was over.