The eye of a vagabond in metaphor

That catches our own. The casual is not

Enough. The freshness of transformation is

The freshness of a world. It is our own,

It is ourselves, the freshness of ourselves

—Wallace Stevens “Notes for a Supreme Fiction”

In my last year as an undergraduate and at the beginning of graduate school I began to study the poems of Wallace Stevens with more intensity. Stevens’s poems and the essays in The Necessary Angel expanded my sense of what could be imagined through a poem. In particular, the idea that modernist poems could go beyond Romantic lyricism to an unanticipated fabrication of the image, which is the case for many of Stevens’s most arresting poems. In “Notes for a Supreme Fiction,” many of his stanzas illustrate discursive gestures which lead to a discussion about poetry’s ability, through abstraction, to please through oblique metaphor and figurative language that “catches” our imagination and gives us, the reader, a new sense of ourselves, a “freshness of ourselves.” It’s the discursive that figured new possibilities for valuing what could be found in poetry. “The eye of a vagabond in metaphor” and “the freshness of a world” struck me as features that make an aesthetic experience exciting, and the poem imaginative. While there are sides of Stevens I can do without (his racism) there are sides of Stevens that taught me so much. I found a sense of alternate turns and twists the poem could take; a poem could conjure quality beyond “the casual” with expansive syntax, tropes, and frames of mind. In the essays, however, I saw yet another Stevens, the ethereal Stevens whose intensity lay bare in the notion that we, and the poem, “live in the mind,” and the idea that the poem is about its “freshness.” I like to think the poem could illustrate the gleeful, eccentric, the wondrous, in figurative language and words: euphony and homophony: the phonetic, the semantic, and the notions of alterity and otherness built into a line.

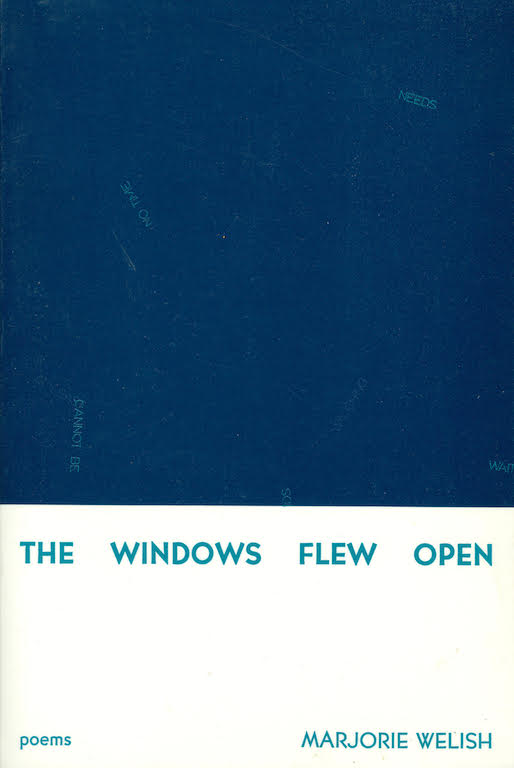

While reading Stevens I was also encountering the poet, painter, and art critic Marjorie Welish both as a poet and as a mentor. It was 1993 and I was attending Brown University’s MFA program. In Welish’s work I saw an embrace of the most wild, abstract and observational in Stevens, informed with her renewed freshness in constructing the image and its possible abstract correlative. She creates her own set of notes in her poems. Her book The Windows Flew Open broadened my universe of what the poem could be and hold as its subject: a language fueled from living in the mind, thinking about gender through an alternative discourse, one punctuated with pensiveness, turbulence, and a kind focus on how a poem can move (to quote Stevens) with language “too constant to be denied” and yet full of an undeniable lyricism that refuses to linger in the personal lyric confession.

This is all to say that this essay is not really about Stevens but about a poet who imagines more for Stevens’s most ambitious feats, a post-structuralist Stevens, the poet Marjorie Welish, who, in her mentoring, empowered me to think discursively and to use that thought as an energetic tension in my work. She was transforming his aesthetic sensibility into something magnificent, through the channels of her sense-making, and what the poem could be after Stevens. She was the first graduate professor with whom I shared my experiences of marginalization, and she corralled them into a new sphere I had not known what to do with: the spaces of cerebral unconsciousness that I wanted to live in, thinking about myself through language differently, thinking about words as many kinds of units, which helped me think about bilingual words, alterity, Hindu concepts, and post-colonial theorizing in the poem. Welish didn’t know she was encouraging me in this way, but she was.

The fourth section of Marjorie Welish’s “Some Street Cries” taught me to note the way the mind and its imagination can mediate the lyric’s subjectivity and what ambiguity the poem can hold. With Welish’s unlikely pairings in her phrasings, she is able to construct an austere distance that creates authorial tension not experienced as “casual” nor personal, but rather cerebral, full of intellectual persuasion, like Stevens. The first line declares the speaker’s intention of “not feeling lonesome,” emoting through the word “scoured” as its condition— an oblique and textured word—allowing her to build more discursive statements of description which seem to think not of people’s mal-intention, but of their problematic “lengthy light,” allowing the other people in the poem to contain many permeable complexities at once. We move into fragments and phrases that delicately declare or suggestively might eventually “cry” through seemingly wooly phrases like “the best of all milk,” “persuasive long pole,” and “conceals a pasture,” to gain a momentum, a hierarchy, and a symbolism: the speaker is defining her values. I’m reminded of scholar Sara Ahmed’s “Where we find happiness teaches us what we value rather than simply what is of value.” We are seeing the value and happiness bestowed on these declarations (more follow): “I have lived and eaten simply/I have leaned against the shape of handsome choices.”

The speaker reveals a contentment and thus offers her contentment to be humbly shared, remarking on choices themselves producing “a pasture you would like.” The poem then turns with the word “outrageous.” The speaker wants to share more than contentment, she wants to share in her own aesthetic productivity whereupon we start to think about larger social issues. The language delves into another kind materialism, that of a painter succumbing to the images and their qualities that define both her canvas and her sensibility, and yet are associative words that lend the reader an expansive view of what the poem might represent: the body of work of the artist-poet: the canvas, the images in a painting, the body of work’s cumulative reception, and the idea of legacy for a woman artist. Upon further reading these words are precise, methodical, and offer as Stevens says, “the mind of the poet describing itself as constantly in his poems as the mind of the sculptor describes itself in his forms,” with authenticity. As a decree around gender, its cries hold forth.

Ultimately, the lyric cadence gives way to formal concerns the speaker has with her value as a poet, artist, and woman, without deliberating the ego’s positionality in the poem. Here the speaker starts with a declaration “I think I shall end…” and moves these “ending” urgencies to life affirming ones without the lyric sentimentality we might usually find—and the lines to a place where the speaker is able to declare her worth through concrete images that somehow move into a contemplative abstraction: “fine milk,” which is both a kind of essentialist metaphor and a visual domestic space of the canvas full of procedural acts that define “eye of the vagabond.”

There is much more to say, and this little essay is a quick study on Welish’s poem and her influence upon my work and me. I am completely enamored with the way many of her poems build their discoveries through a pristine and opaque sense of diction, and infinitely nuanced language. Marjorie Welish, in writing about Robert Rauschenberg, discusses “Notes from a Supreme Fiction” when framing Rauschenberg’s newer works in an exhibition in Texas. She cites section 10 of “It Must Change.” In this, I recognize a kinship with him that we also find in her poems: for her poems are also, like Rauschenberg and Stevens, daringly insightful and are a “layering of principles and of nature and culture in a rigorous—and beautiful—way.”