The Million Book Project is the brainchild of poet and legal scholar Reginald Dwayne Betts working under the auspices of Yale Law School‘s Justice Collaboratory and with financial support from an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant. The primary goal of the project is to curate 500 books to be placed in prisons throughout the United States. These “Freedom Collections” will anchor the project, and will contain seminal works of poetry, literature, history and social thought. Inspired by the important role of reading during his own imprisonment, Betts envisions these collections in the housing units of penitentiaries where they will become a part of inmates’ everyday life. Each library will have a museum-like catalogue with descriptive micro essays written in up-to-date language about each book.

The project also encompasses plans to expand the world view of those serving time. Fifty-two literary ambassadors, published authors linked to each one of the states, plus Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, will present literature to prisoners in their territory through visits and mentorship. Through the grant, Betts hopes to partner with prison authorities and other organizations doing similar work to develop book clubs within prisons in order to encourage the idea of reading in concert. Perhaps the most ambitious element of the Million Book Project is Betts’ plan to develop a literature syllabus accompanied by video lessons, to tutor prisoners interested in learning to read deeply and to analyze the structure of writing.

The Million Book Project was announced by the Mellon Foundation in late June 2020 and is an important part of the foundation’s move toward prioritizing social justice in its grantmaking.

This interview was conducted by Mariann Lynch in the winter of 2020, and has been edited for clarity.

ML: Thank you for agreeing to do this interview.

For Poetry Daily’s new series of interviews, we want to highlight the work poets do in the community and so we’ll focus on your Million Book Project. First, though, I was so affected by your memoir, A Question of Freedom, about your time in prison, and would appreciate it if you would share with our readers the facts you consider to be most relevant about mass incarceration in contemporary America and what you think will need to happen for Americans to finally think differently about mass incarceration?

RDB: I think, actually, “mass incarceration” is one of those phrases that we should banish. I think it’s one of those things that would be an affront to George Orwell — the notion that mass incarceration is a word that hides so much. I would much rather have people think about the experience of prison articulated in books, articles, and podcasts really viscerally. I would want somebody to listen to the Ear Hustle podcast made out of San Quentin and begin to grapple with what it means to experience prison and not just throw this tagline on it.

I do think that we incarcerate far too many people. I think the reason we have trouble addressing it is somewhat technical. We live in a country with fifty different states, and it’s not even just fifty different systems, it’s a different system, literally, for nearly every city in the country. So, things become far more complicated.

But just think about the values that the country seeks to advance. Understanding what it means to spend time in prison will help, I think, become a corrective for how easily we are willing to allow brutality to take place. Of course, the brutality that we allow is completely independent of the horrific things that people sometimes do to land themselves in prison.

ML: Please tell us the story of The Million Book Project and your vision for how it will alleviate the effects of the inmate experience?

RDB: Yeah, I mean the Million Book Project is principally an argument that books matter, that books are pathways to freedom. We’re curating a library of five hundred books. We call it the Freedom Library, and we’re putting a bookshelf with these books in housing units in prisons in every state in the country, as well as Puerto Rico and Washington DC.

The truth is that we believe books make the kind of conversations happen that help people think about themselves and see themselves in different ways. I was reading Victor Frankl’s book, Man’s Search for Meaning, and one of the things Frankl says [referring to his time in WWII concentration camps] is that there would be times he could get lost and others could get lost just completely. He says that they would be on these tracks and they would be on these brutal marches and they would just get lost in the memory of an idea or a book or loved one. And it’s all building a muscle, but you need something in prison to help you exist, not independent of how bad things are, but to help you have something that rises adjacent to that to remind you there is something else on the other side.

So that’s what we’re trying to do and, of course, part of that is bringing writers into prisons. Part is creating a podcast so people in prison can experience some of the world they can’t experience right now. And frankly, part is forcing the people on the outside to really think about prison as a part of a community because right now too many of us have no responsibility to do so. We are unaware of the responsibility we have to recognize that prisons are in our community, whether they’re five miles away or fifty miles away.

ML: What do you see as the biggest challenge to getting books to prisoners and what kind of responses has the project received from the public and from corrections authorities across the country?

RDB: I mean, money, you know, money and resources. I don’t think there are real challenges to getting books to prisoners. I think that is just work…. This is not a job you find advertised on the Internet. So, you need a person to be able to make the phone calls, to be able to coordinate with different institutions. And if you want the books to be free, and you also want the books to be cohesive or loosely cohesive or part of a set, I mean, then there are some logistical things you have to do. We put 2.5 million people in prison. I’m not going to sit here and pretend like it’s hard to put 2.5 million books in prison.

I put together a team, and we are trying to demonstrate that we can make this happen. We can make it happen and create something that’s beautiful. Even the titles of the books being considered: The Luminaries, Moonwalking with Einstein, Absalom, Absalom, Black Boy… are like a poem. Imagine, The History of Scientific Revolutions is a book somebody might look at and say “What? What is a scientific revolution? Let me check this out.”

I don’t want to make light of the challenges that we’ll face, but compared to the capaciousness of the written word and all it has been able to capture, I think that we’re okay. I’m quite hopeful every day when I wake up to do this.

I think the only people who have a better job than me are librarians, you know? So, it’s good. I like my job because I get to cultivate… I get to be really idiosyncratic and in some way selfish [because] not only do I build this thing that I want to exist, but as we work on building the library I get to have conversations about books with people who I think are absolutely brilliant and amazing.

ML: So the challenges are manageable?

RDB: Yeah.

ML: And the public response and the response of prison authorities, what are you getting?

RDB: I’m bringing a project that centers on the love of books. We’re bringing thousands of carefully selected and curated books into these prisons and saying: this is a gift, for the men inside, for the women inside and for the men and women who work here. There is no cost for the system. Simply a gain. A profound gain, if you ask me. The response right now by prison authorities is as expected, I think that they’re excited about the prospect and the possibility. I think they are encouraged in some ways. Of course, there are challenges from their point of view, but those challenges are just par for the course — like how are you picking the books, how are we going to handle security issues, things like that. But they’ve been excited.

ML: That’s encouraging, because I have this mental image of the warden. And that’s who I think of as the corrections authority and in half the media that I’ve consumed the warden is usually kind of a bad guy. And you’re saying these people are excited about the idea.

RDB: I think that the whole project encourages us not to try to characterize these prison officials in one way.

The Directors of state Departments of Corrections have a really complicated job. Wardens have a complicated job. Correctional officers have a complicated job. This is a project about people inside. And more than any of us, who aren’t prisoners or correctional officers, or wardens or whatever — these folks are all inside. This project is about them. Not just the prisoners. But everyone who understands what it means to hear a cell door closing. You’re in the middle of a global pandemic, you’ve had to reduce the programming opportunities for prisoners. I mean, this is beneficial when prisons are operating the way they normally operate, but in a world in which resources are so constrained, this is… I like to think of it as a gift. Okay, maybe not a gift to them, but here’s an opportunity for us both. It’s a feel-good project.

ML: Are you getting pretty good responses throughout the country?

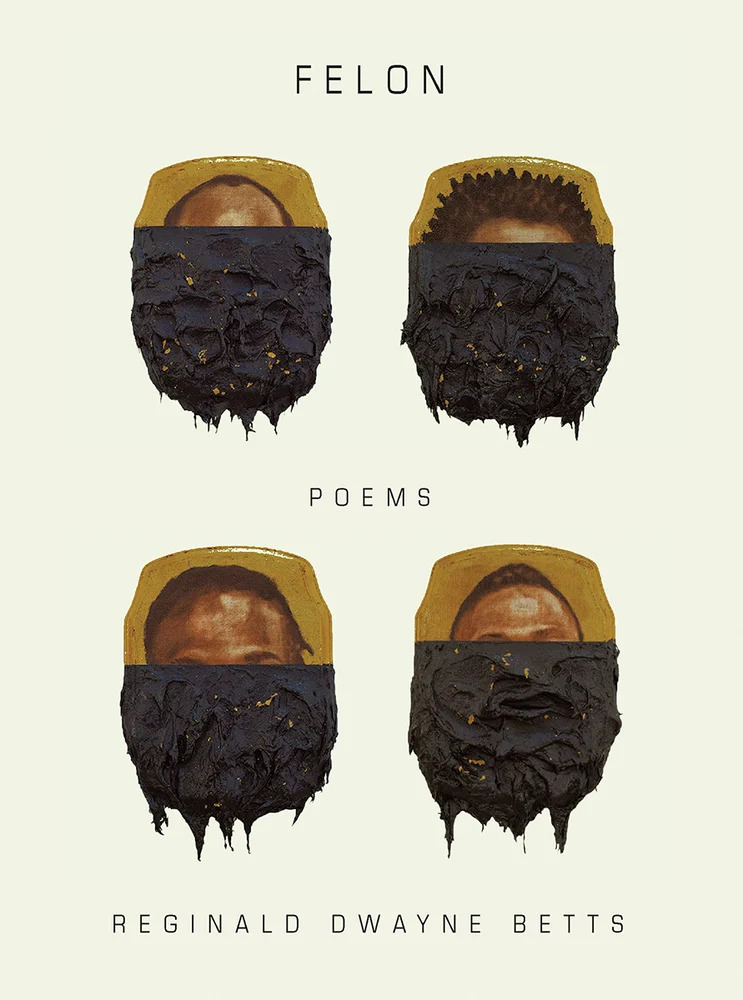

RDB: Yeah, yeah. I mean, you know, “throughout the country,” I don’t know what that means. The country is big. This is a slow walk. So far we’ve disseminated around two thousand copies of Felon, my book, and we’ve given away a couple hundred copies of Rion Amilcar Scott’s Insurrections. We — and by we I mean myself and my co-host Elsa Hardy and our podcast producer Erin Slomski-Pritz — have recorded three podcast episodes so far and have more interviews on the calendar. We are working on finding ways to broadcast the podcast inside.

This is a big and funky and radical project. And so it gets walked out slowly. And one of the things I’m learning is that a lot of times we try to conceptualize this work having not brought anything to scale. I didn’t understand what it meant to bring something to scale. But I think a lot of people who criticize different kinds of projects also don’t understand what we mean. We’re putting a million books in prisons, and that’s not even what I would imagine to be the kind of scale that I want a project like this to exist on. We want this Freedom Library to serve the same purpose as the libraries you find in people’s homes.

If we’re going to put people in prisons, then we should have Freedom Libraries in every prison with them. We should have a beacon of freedom that they see on a regular basis. Books invite people to self-reflect, to imagine different worlds. This project is a testament to the eye-opening possibilities that literature gives us…

ML: Brilliant. Okay, so can you describe the process of curating the library?

RDB: We have a survey available and we are still trying to make the survey go viral. The survey has been a real iterative process. And one of the reasons is because we asked survey participants to tell stories, and the stories are fascinating and become a rabbit hole into why a single book matters.

Then we’ve had these book circles, which have actually been fascinating because we put three or four people together and we usually allow one leader to organize the other two or three people, and they just talk about books they love. It is something exciting to hear people talk about books they love, especially smart people…

I’m going to tell you what Wesley Morris said about Angels in America. He said, “I could read that every day for the rest of my life and never feel like I’ve gotten to the bottom of it. It is one of the most inspirational things I’ve ever read. It is one of the great attempts to reckon with a moment in American life. But by wrestling with that American moment, you must reckon with the centuries that lead up to it and help produce it. There is so much wisdom in this anger, how you take ideas and wrestle with them in a melodrama is really hard to do, and this does it and it’s great.”

ML: Nice.

RDB: You know, it makes you want to read the book. I mean it’s as simple as that. It’s like you hear something like that and you think, I will pick that book up. If you just looked at the title, you might not. But [Morris’s] description right there deeply moves me. And so we created book circles where we give people opportunities to talk about the books they love and we get the suggestions they contribute. And then we say, “Oh, that’s one. That’s one. That’s one. Then, I get books out of my own head, and we say gotta have that, gotta have that, gotta have that.”

And then internally we have a whole bunch of arguments about what should be there and what shouldn’t be there. So we build a list out: fifty, a hundred, a hundred fifty, and we give it to a curatorial committee member in advance. Then we set up a conversation with them and they kind of go through the books on the list. And then, in the process of going through the books on a list, people always get ignited — “Oh, remember this book?!” “Nah, not that book. That book, and here’s… and here’s… Have you ever read this?”

The crazy thing and the wild thing about a bookshelf being a place of possibility is you always have books you’ve read and books you haven’t. So when curating this library, I’m not even just curating it for people who are incarcerated. I’m also curating it for myself. I never read Angels. You know, some books I have read and I get hip to, I get reminded of. But there’s also a lot of books that folks bring to the forefront that I’m like, “Oh man, that’s my gap,” you know, and this is nice.

So those are sort of the primary ways. And then the final way is that once we build the whole set, once the whole 500-600 books are picked, if you are one of our institutional partners, then we sit down with you and over the course of three hour-long conversations, we look at the whole thing and build a case for what the whole library is doing and what it’s not doing, and take a final hard look at the gaps that exist.

ML: How can Poetry Daily readers help the Million Book Project?

RDB: Go to the website. Check out what we’re doing, read the books that are in our Freedom Library. Give them to friends. And, frankly, donate.

ML: When we spoke earlier, I asked a question that you said was baffling. So let’s have another go at it. Will you share with our readers a time when a book allowed you to transcend your experience? At the time, you expressed uncertainty, but then told a story about a mango.

RDB: Oh man, that was a good story, too.

I remember exactly what I was saying, because it’s like somebody asked me if a piece I wrote was cathartic. And I was like are you asking me if the piece made me weep. If you want to know if I cried while writing it, then yes, I cried while writing it. But if you’re asking if that crying somehow released some tension that allowed me to become somebody different afterwards, then the answer is no. I don’t actually know what people mean when they say cathartic. It’s the same thing when you say “transcend your experience.” I mean, I have read books that allow me to feel like I am not in a place where I am.

On election night at two o’clock in the morning I started reading Man’s Search for Meaning because I couldn’t deal with watching states like it was a basketball game. And Frankl’s book transported me to a world that was unlike anything I’ve known but so familiar to some of the places that I’ve known. It didn’t let me transcend anything but it reminded me.

And I remember that thing I said to you. I had a mango in prison and it was the first time I had a mango in my life. I had nothing to compare it to. And also, I had no guide for the experience. I had a tray. I’m in solitary confinement. The mango is red and slightly green like an apple in the fall. I bite into and taste a sweet flesh, but it’s a rubbery piece and realize that you could peel off the flesh. I was sitting on my bed at first with the plastic tray on my lap and it was messy. So I get up and I’m eating a mango over the toilet/sink contraption and there are juices going down my face and my hands and it’s like the most delicious thing I’ve ever eaten, and for that moment, it really did make me transcend this space because I had no idea where I was going. I didn’t know that this was a fruit of the Caribbean. So I couldn’t name the place I went to in that moment. What brought me back to reality was the bone in the middle of the mango. It was so delicious, and I know it’s not going to happen again. I intuitively understand somebody has made a mistake in giving me this small piece of deliciousness. And I’m scraping the bone with my tooth and I chipped my tooth on the damn bone. And that’s what brought me back to reality.

ML: What a great story to end on. Thank you for your time, and best of luck with the project.

RDB: Thanks, you have a great day.

Mariann Lynch is a retired middle-school teacher pursuing coursework in poetry at George Mason University. She holds undergraduate and graduate degrees in anthropology from the University of Pittsburgh.