“Now they zip you in to a body / bag,” Michele Glazer writes, “one size fits all. / / We place white peonies on your chest. / See what you lost when you lost this world / / don’t go.” This is what the death of a loved one looks and feels like from up close. Dedicated to the memory of her parents, Glazer’s riveting fourth collection features poems that seem to have emerged from the kind of gravity that the late poet C.D. Wright evokes when she suggests that poetry is “the language of intensity. Because we are all going to die, an expression of intensity is justified.”

I first opened fretwork three weeks after my father’s unexpected death. I had to stop reading after the second poem. I returned the book to its shelf and distracted myself with a gossipy novel. A few months later I tried again and found fretwork to be a necessary companion to my evolving grief. And yet, Glazer seems to have written this book fully aware that the only manual for grief is the one the grieving person writes in the midst of their suffering. “We have arrived at what we dread,” she writes, “the / diminution of loved ones, livid / and unmistakable lapses…dread: dread / that is the one certain shore.” It’s a shore that Glazer navigates with deep curiosity. It’s also a shore she inhabits with people she loves, sometimes from a distance. But, she writes, “…it helps me to think of distance as / a place to meet…” In “Clench,” a poem about her father’s cremation, Glazer writes:

From every direction

You are one

Long night poured into another night.

While your feet

Were still recognizable as feet I

Wanted to place

The bottoms of my own against them.

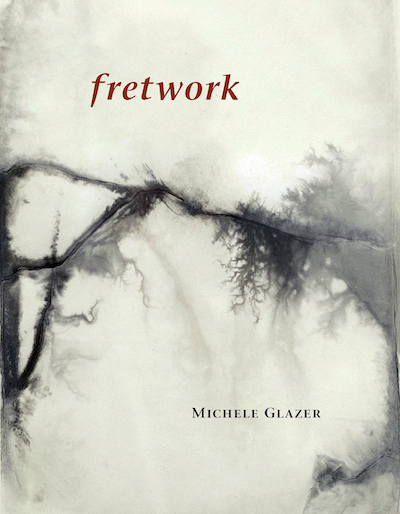

In an explanation of the process the multidisciplinary artist Saul Melman uses in his Anthropocene Series (featured on the cover of fretwork) Glazer writes, “The artist sets a process in motion, but the materials have the last word.” It’s a deeply instructive metaphor for how Glazer allies with language to create poems that feel and sound as though she is tapping into a frequency just beyond herself. Like a bonsai expert trimming the tiniest branches in order to create the shape the tree wants to be, Glazer listens to the poem as it tells her how it wishes to evolve. As any artist knows, such generative acts require a fierce dedication to process and a rich imagination. In the book’s stunning finale, “Path of Totality,” Glazer speaks of “the last desultory breath.” Is the poet referring to her own breath, held as she stands awestruck before a total solar eclipse? Or is she recalling the last breath of one of her parents? Is there a difference?