GETTING PERSONAL

My friends and I have a repeated joke: the older we get, the more like ourselves each of us becomes, in our different ways.

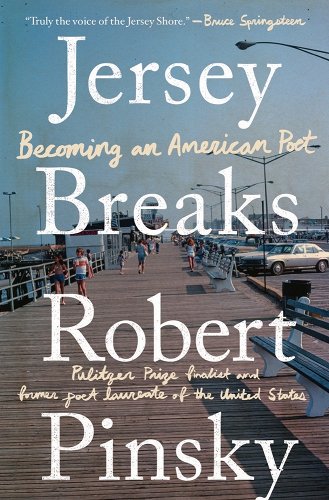

For example, I call my recent book Jersey Breaks an autobiography. “Memoir” is the more customary retail category and literary term publishers use, maybe to imply a French, gossipy and reminiscent warmth. But I prefer the coolness of “Autobiography.” It feels personal, but by surprise, with a deeper inner person hiding behind the cold, objective-sounding surface of “biography.” Better a covert arrogance than a conventional self-disclosure.

Here’s an example of “covert arrogance,” from Jersey Breaks: when I was twenty years old, I applied to a foundation for money I was hoping to live on for the year after I graduated from college.

When, after the customary month or two of suspense, mail arrived from the foundation, with a high-class return address, I did not open the envelope. I put it on the mantel of a bricked-in fireplace, and there I left it, address outward, for several days. Taking my time asserted, in a childish and heartfelt way, that I was not in the power of that well-meaning institution. Behaving as if I was worth more than any Foundation reassured me that it might be true. The little gesture was personal to a fault. It was covert, in that only one person, the one I was living with, was aware of it.

That juvenile performance of restraint, or belief in myself, or whatever I thought I was doing, of course reflected a wealth of petty wounds and resentments—my particular theater of the accumulated humiliations and compensating fantasies of any life, peculiar to our each one life. Or if not a theater, a tavern where you can be drunk on your personal cocktail of blended arrogance shaken with despair and finished with a dash of bitters.

Now, in my eighties, I halfway forgive the kid his pointless though impressive feat. In the eighth and ninth grade, on his report cards he received grades of C or D in something called “Citizenship” with a capital “C.” It offended his patriotism. Why couldn’t they call it “Comportment” or “Conduct”?

Another example, also from a sentence in Jersey Breaks: the high school Spanish teacher and football coach Army Ippolito, a classmate of my mother’s at the same high school, saw her on the street and told her, “Your son doesn’t want to get an ‘A’.” Army gave me “B” in Spanish because I was eager and resourceful in conversation, but did not score well on his grammar tests. I was often too proud or lazy to use teeny, concealed cheat-sheets for those quizzes, as nearly everybody did. Army Ippolito had my number.

In a much later version of whatever that twenty-year-old thought he was doing, my first interview about being appointed Poet Laureate of the United States, I noted that the term “laureate” was traditionally associated with mediocrity. The list of British Laureates was laughable, I pointed out, and they were servants of a family at the apex of an obnoxious class system. That was my slightly but not entirely more grown-up way of scorning high grades, and those who award them.

A way to make good use of the poshlost Laureate title was the Favorite Poem Project.

My friends think I have written about the FPP enough. Possibly too much, I can imagine them saying—a good example of Robert becoming more and more who he is, as he gets older.

But here I go again, I hope in a different way.

I tried to keep the videos of different readers presenting poems they admired impersonal, in certain ways. I avoided using the project to promote work by poets I knew—still less, my own. The videos we shot were not governed by my mere taste. They reflect my standards. The same goes for the anthology published by Norton, with each poem preceded by headnote quotations from readers.

Thanks to the brilliant producer Juanita Anderson and the remarkable filmmakers Juanita recruited, all the segments remain useful as well as superb. Many of them are memorable: I think of Emiko Emori’s video of a Cambodian-American high school student reading “Minstrel Man” by Langston Hughes, David Roderick’s video of a bomber pilot who served in Vietnam reading Yusef Komunyakaa’s “Facing It” at the Vietnam Memorial, Natatcha Estébanez’s videos of a U.S. Marine reading “Politics” by William Butler Yeats, and of a construction worker reading from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.”

Underlying those good works, my own, personal history of resentments, prejudices and aspirations are—I believe and pray—invisible. The project is democratic yet elite, in a combination I value. It is patriotic, demonstrating something admirable in American life, based on the dignity of individuals and the presence of art: not a program of the academic realm, and not a product of the entertainment industry. No professors explaining the poems and no actors performing them: just readers. It was not the kind of high-budget undertaking that large foundations find prestigious. Our budget was too low for them—so little money for such good results, with so few non-profit experts: for those large foundations and their bureaucracies, the FPP was kind of bewildering, maybe even embarrassing.

In other words, the sullen teenager in me generated a motive, but he was limited and kept off-stage. He was satisfied, I guess even gratified, but thanks to the people involved, and to the fundamental art of poetry itself, he did not mess up what he motivated. Thanks be.