It’s commonplace to claim that all poems (or all great poems? . . . or all bad poems?) are about poetry. Here is a poem explicitly about prose:

JOHNSON ON POPE

—from The Lives of the Poets

He was protuberant behind, before;

Born beautiful, he had grown up a spider;

Stature so low, he could not sit at table

Like taller men; in middle life so feeble

He could not dress himself, nor stand upright

Without a canvas bodice; in the long night

Made servants peevish with his demands for coffee;

Trying to make his spider’s legs less skinny,

He wore three pair of stockings, which a maid

Had to draw on and off; one side was contracted.

But his face was not displeasing, his eyes were vivid.

He found it very difficult to be clean

Of unappeasable malignity;

But in his eyes the shapeless vicious scene

Composed itself; of folly he made beauty.

I first read “Johnson on Pope” by David Ferry in his 1960 first book, On the Way to the Island. I felt immediately that I had learned something about the art of poetry. Ferry’s poem demonstrated the crucial difference between prose and poetry as vocal: a matter of sound. That limited, technical point had its power.

Possibly the poem also made me think again of Emily Dickinson’s words: “Tell all the truth, but tell it slant—Success in Circuit lies/ Too bright for our infirm Delight/ The Truth’s superb surprise.”

I may or may not have actually read Samuel Johnson’s sentences about Alexander Pope, but as an earnest, bookish poet in my twenties I could imagine them. David Ferry had converted them into iambic pentameter and added some erratic but unmistakable rhymes. That vocal transformation made Johnson’s asserted, documentary truths into something illuminated aslant, at an angle through darkness.

How had the sound of verses made prose from the eighteenth century into a modern poem I would not forget?

Ferry’s audible transformations, by making the words and images his own, had also separated the emotional meaning into three characters: Pope, struggling with his bodily needs and limitations; Johnson, writing about Pope with candor and sympathy; Ferry, slanting and orchestrating the stories of Pope and Johnson toward his own point, so intense it feels confessional, about folly and beauty, malignity and shapelessness: three writers, each dealing separately with the describable but mostly insoluble predicaments of art.

Many years later, I learned that the Nicaraguan poet Carlos Martínez Rivas (1924-1998) had entitled his book of poetry La insurrección solitaria. The motto of a poetry festival I attended presented that idea as a sentence: la poesía es insurrección solitaria. Poetry is a lonely insurrection, or depending upon your translation, a solitary revolt. I believe that the vocal nature of lyric poetry emphasizes the individual human body, or each body capable of sounding the words, or signing them or singing them: that is where the poem happens. Ferry’s poem, by giving breath and presence to Johnson’s superb prose about Pope’s physical plight, makes the plight an epitome of poetry’s nearly impossible effort.

Tell all the truth but tell it slant—. The moment I begin saying to myself Emily Dickinson’s first line, my tongue flicks rapidly to the roof of my mouth for the first sound in the first word “Tell.” The same exact little movement happens at the end of the line’s last word, “slant.” In this pre-industrial, bodily way the reader becomes the poet’s instrument. In a way, it is as though they were one. But in another way, the bodily nature of the line enacts the double solitude: the reader’s body absolutely itself, utterly separate from the equally solitary poet who made the line: solitaria. Ferry’s poem is about the empathic loneliness Johnson’s prose suggests but cannot embody.

I don’t know if this poem’s use of prose is similar to the contemporary tradition of erasure, or the opposite. I don’t know how Ferry’s transformation is related to the modernist tradition of the prose poem. Both considerations seem relevant. Here are a couple of samples from Johnson’s prose that Ferry uses:

The person of Pope is well known not to have been formed on the nicest model. He has, in his account of the Little Club, compared himself to a spider, and, by another, is described as protuberant behind and before. He is said to have been beautiful in his infancy; but he was of a constitution originally feeble and weak; and, as bodies of a tender frame are easily distorted, his deformity was, probably, in part the effect of his application. His stature was so low, that to bring him to a level with common tables, it was necessary to raise his seat. But his face was not displeasing, and his eyes were animated and vivid. . . .

When he rose, he was invested in a bodice made of stiff canvass, being scarcely able to hold himself erect till they were laced, and he then put on a flannel waistcoat. One side was contracted. His legs were so slender, that he enlarged their bulk with three pair of stockings, which were drawn on and off by the maid; for he was not able to dress or undress himself, and neither went to bed nor rose without help. His weakness made it very difficult for him to be clean.

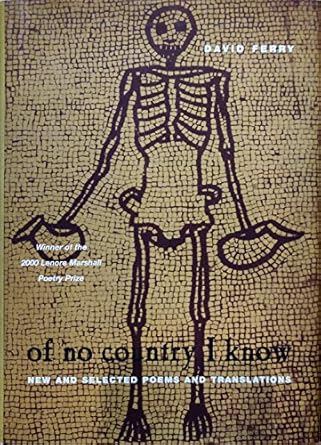

In 1755, Samuel Johnson published A Dictionary of the English Language, which set the style and manners for all of its successors, continuing into the present. His Lives of the Poets (1779-81) with its mixture of biography, annotation and criticism, created an enduring pattern for writing about poets. The prose is brilliant, detailed, calm and monumental. David Ferry’s poem shows how even great prose can be used as a source for something solitary, told aslant, heartfelt and intensely musical.