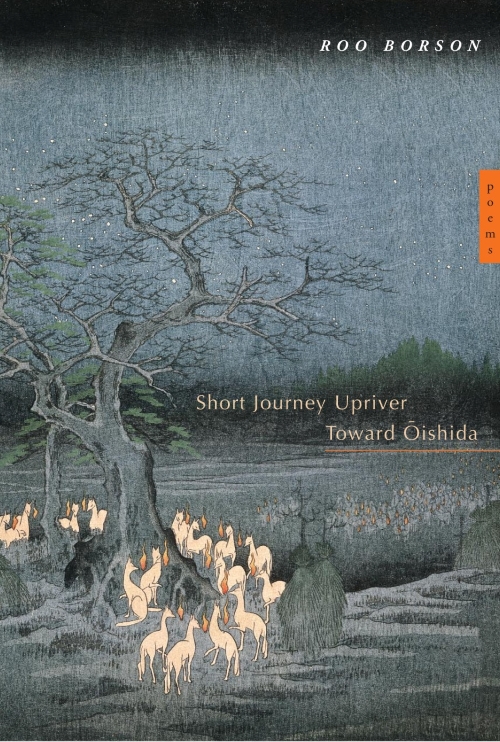

Written in the spirit of Basho’s famous journey to the far north, Roo Borson’s Short Journey Upriver Toward Oishida artlessly folds together the reflecting mind and the wayward, brimming world. It’s a book I dip into now and then, when I desire something intent, nascent-seeming, clear as water. During the pandemic, it seemed a particular source of practiced grace. Writing about nature is difficult; it’s hard to do without resorting to cliché, without being obvious or precious. But Borson doesn’t seem to worry about the burden of human consciousness in her registrations of nature; in “Summer Grass” she writes,

The swans are reasoning beings;

the young cygnets, hatched from pins

and old mattress stuffing, bright-eyed, learning

what has bread, and what doesn’t.

She finely accumulates detail in her descriptions, absorbing the tensions of her own human awareness of nature, and the notions of animal consciousness and even the absence of consciousness. She manages to remain both reverent and witty; in the same poem, she interjects, “Do you still love poetry?”

As with Basho’s journey, hers is studded with passages of prose that use the language of a dairy or personal travelogue: casual, seemingly artless, but self-conscious:

The grasses are tasselled with seed, the crickets beginning, in stops and starts, suggestive trills. All of this happens in memory of course, recalled under the lamp’s warmth as you lie in bed with your eyes closed, too tired to read. Later they’ll sound more insistent: exploratory, expository, epistolatory, before become exhausted.

Prose passages like this one can seem like dummy runs for poems, or rather, that is their contrived-yet-guileless effect. Somehow, her work reminds me that we don’t really count in the scheme of things. And yet that news is startling each time, a kind of friendly pleasure in a book filled, like Basho’s, with death and partings and weather.