In 1945, the Scottish writer Nan Shepherd sent a manuscript of The Living Mountain to the novelist Neil Gunn. His response read in part, “[Y]ou deal with facts. And build with proposition, methodically, and calmly, for light and a state of being are facts in your world.” As her title suggests, Shepherd experienced her beloved Cairngorm Mountains as a living thing, a massive interdependent system of rock, wind, water, soil, plants, animals, and light, a perception so far ahead of its time that it wasn’t published until 1977, and only in this century has found its place with readers worldwide as possibly the best book on mountains ever published. A Taoist or Buddhist work that never mentions either; a wartime book that scarcely mentions war; a work of deep ecology before the phrase was coined. Shepherd’s project, in her own words, was to know the “essential nature” of the Cairngorm plateau, “To know, that is, with the knowledge that is a process of living.”

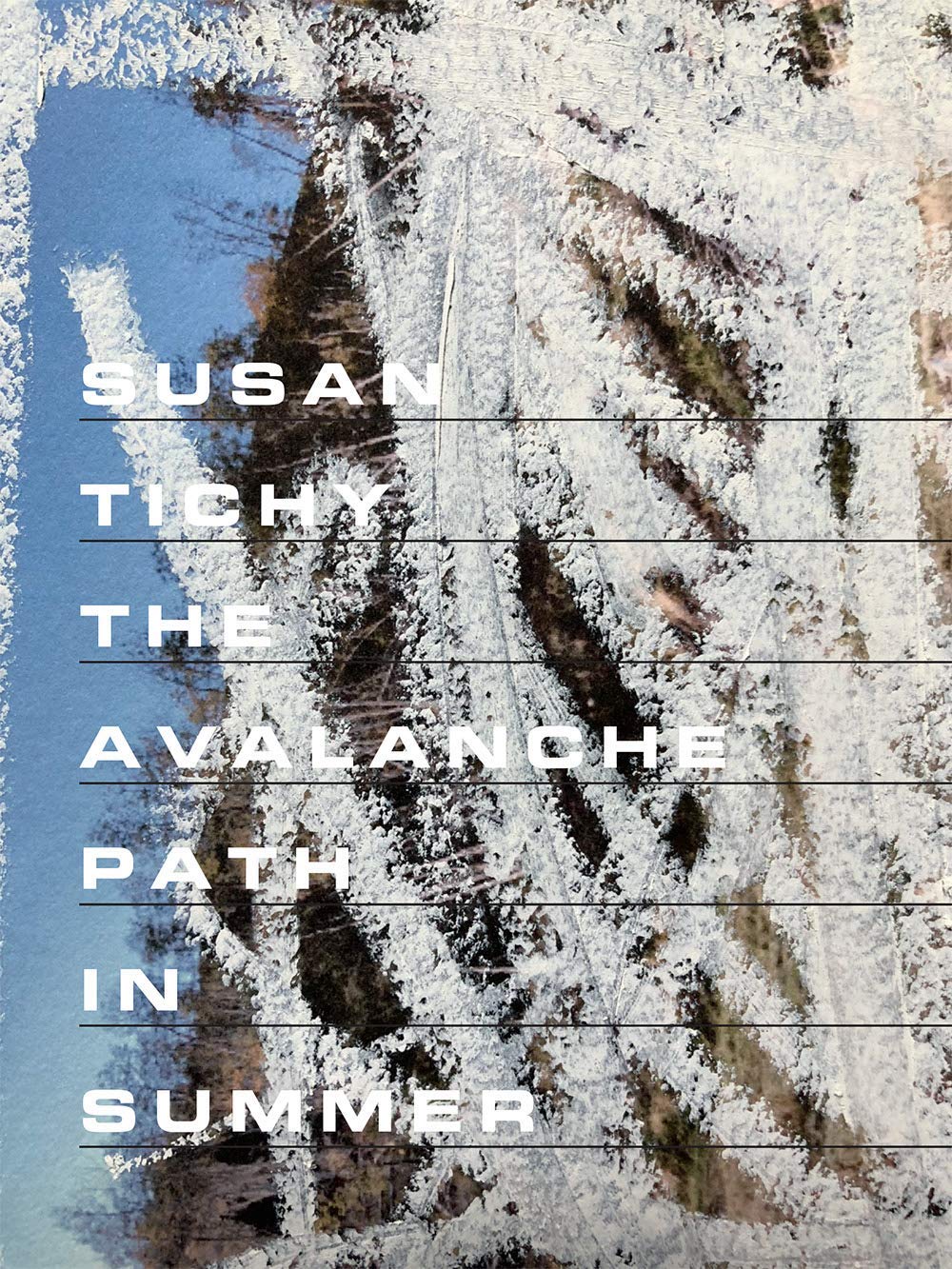

For the first thirty years I lived in and with mountains I resisted writing in/from/about their presence. I couldn’t objectify them, thingify them. Only as I aged and began, in some ways, to lose them, did the need to write outweigh impossibility, and even then The Avalanche Path in Summer took ten years to evolve. “’In Country That Is Rough, But Not Difficult, One Sees Where One Is & Where One Is Going at the Same Time’” was one of the last written. The title words are Shepherd’s; quotes within the poem are from other mountain writers. All I wanted for the poem was openness, a merging of muscle-memory with the skittering of words down the page, to know as a process of motion.

My home mountain range, the Colorado Sangre de Cristo, is an 80-mile fault-block uplift, with ten summits over 14,000 feet. Its surface is largely metamorphic conglomerate, rocks that display their biography of sedimentation, fracture, pressure and heat, chemical transformation, upheavals from basement to surface…in turn broken down, moved, carved, and placed by violent uplift, the abrasion of ice, and more recent actions of gravity, water, and snow. Walking there for the last forty years has helped me learn that place is neither fixed nor purely spatial, but temporary and temporal, contingent and unstable, an intersection of forces I happen to encounter (and take part in) during my brief time on earth and briefer time as walker through a landscape. Here & now is a knot, and all its strands are moving.

A poem, too, is a series of intersections. To be like a mountain, a poem must be in ever-motion, unclosed and unfinished. To be like a mountain, a poem must/might be its own metamorphic conglomerate, swallowing fragments of what came before—texts, body memories, images—transforming them by pressure and heat into some new thing.

Collage poetics allows contradictory and contested fragments to co-exist, maintaining their scent of autonomy, and constantly in motion relative to each other. The spaces between them are not vacuums, but fields of energy, uncertainty, and change. Thus, the metapoetic space of a poem can create a structure that is also motion.

And yet: each day on foot in the mountains includes an excursion into wordlessness. A poem, whether written in situ or after, is a return. All the poems, therefore, encounter/embrace/mourn the gulf between being there and thinking about being there.

What I want for readers is to be carried, line by line, in and out of thingness, in and out of sound and play, constantly shifting among sensory, narrative, and abstract information, in a series of intersections, of meeting places. By moving with the poem and jumping its gaps, readers can become co-creators, letting rhythms carry thought as a body carries mind, through a place where light and a state of being are the overwhelming facts.