1.

I am interested in the way translation challenges traditional models of authorship and the idealization of the self-contained text. Translation takes place in a space of corruption and transformation, what Joyelle McSweeney and I have called “the deformation zone.” Translations are acts of mimetic excess, they generate too-much-ness, volatility, transformation. In order to maintain order, some writers try to contain this excessive energy by trotting out the old demand for a “faithful” translation, idealizing the illusion that somehow a translation can (and should!) be tied to the original as in a legal marriage, or the idea of “equivalence,” as if translation could be made to follow a proper exchange rate. But translation wreaks havoc on official exchange rates and economic ideals. Translation is not an economical act; it’s an act of “transgressive circulation.”

2.

Despite being one of the most renowned and influential Swedish poets of the past fifty years, Ann Jäderlund writes inside deformation zones. Like one of her major influences, Gunnar Björling (whose selected poems remixed excerpts of all his previous books into one long poem, and who liked to have his young boyfriends do erasures of his poems as part of the revision process), Jäderlund cycles through source texts–including her own work–as she writes her poems. These texts may include nineteenth century novels or medieval religious texts; or, as in Lonespeech, they are the correspondences between Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann.

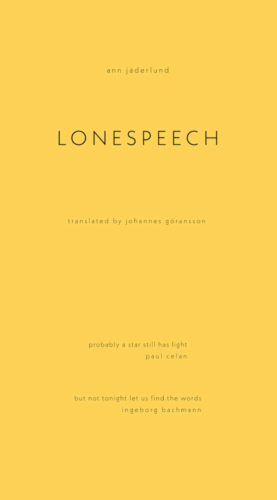

In Lonespeech, unlike in past books, Jäderlund announces the major sources of the book by including quotes from Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann on the cover of the book–making these two influences visible, so to speak, and rejecting her own claim to absolute originality. From Celan she takes the phrase: “probably a star still has light.” And from Bachmann she takes the phrase: “but not tonight let us find the words.“ The reader knows from the start that Jäderlund’s poems are deformations of the famous German-language poets. These are poems as translation.

The two quotes not only introduce themes (of darkness and words, silence and communication), but, in their simplicity and brevity, they share a stylistic affinity with Jäderlund’s book. There is a complex, dynamic play between Jäderlund and “the original.” These poems also do not follow the easy conceptual model of appropriation. The phrases by Celan and Bachmann seem almost as if they were written by Jäderlund. The influence between texts seems to flow in mulitple, volatile, anachronistic directions. It’s perhaps even wrong for me to say that the poems are based on Celan’s and Bachmann’s correspondence. The correspondence is one source, but from these letters, Jäderlund’s poetry is brought into contact with Hölderlin, Heidegger, Shakespeare, Rilke and others. Like Manny Farber’s infamous concept of “termite art,” Jäderlund’s writing “goes always forward eating its own boundaries.”

3.

Like Björling’s poems, Jäderlund uses simple words like sun, tree, eye. It seems that the poems should be very simple, but something is off about the syntax. There are strange tweaks and torques that generate a force, what she in another poem in Lonespeech calls “omklar” (“clearabout”) and in another “clear velocity.” The poems are “clear” but a clarity that moves “around.” But it is precisely its “aboutness” that gives it such a force. Both of these words also point to another feature of her work: precision. The poems are volatile but precise, concentrated.

To translate Jäderlund means to pay utter attention to the order of the words. We can see the combination of simplicity, concentration and deformations in the poem that begins: “Not here/I hear it.” The first two lines may appear to be simple, but they are not. We could interpret the beginning as “I don’t hear it here”. But that is not what the poem says. Rather, it suggests that the speaker may not hear it “here,” but she might hear it “not here,” i.e. in negation. The poem (and perhaps the entire book) is about “ljudet för mörker”–“the sound for darkness,” what is found in negative space. Again, details matter. It is not the more expected “sound of darkness” but “for darkness.” The “dark” sound functions like a word (as in ‘the word for darkness is…’). And there are “so many words” for this darkness; as if the darkness comes from an excess of signification (a strange realization for such a short poem) that surrounds the poet and the reader.

As Iloe Ariss and Venya Gushchin pointed out in their review of Lonespeech, Jäderlund’s motif of “darkness,” and dark sounds and words, invokes Celan’s famous poem “Corona,” which Bachmann later invoked in her poem “To Speak Darkness.” Jäderlund’s poem doesn’t merely allude to these poems, but seems in part to be about reading–trying to metabolize the two older poets’ work. She transforms their words, their dark sounds–but she is also transformed by them. In the deformation zones of poetry, it is not just the “original” text that influences the translation, but also the other way around. The translator is influenced by the foreign text which is influenced by the translator’s sensibility. Transformation is constant.

5.

Lonespeech is full of lines that could be said to be metapoetic descriptions: the poem is a voice that “burns”, poisons “with clear velocity,” speaks, fails to speak, “runs” like lard, “goes in the aorta, “hides a dark sound,” and “is burst.” The poems conceive of poetry as something volatile, violent, sublime. The poems permeate and transform. The poems, the poets, the readers are all permeated in a deformation zone of language, nature, sounds. The poem both goes around us and poisons us, bursts open in us.

In her article “Listen or Die,” prominent Swedish critic Sara Abdollahi Lekta describes how overwhelmed she feels by the book: ”I’m lying on the couch, the one I lay on when I first started reading Jäderlund. I’m afraid, transparent, existentially alone and drained.” Jäderlund’s simple little poems can really overwhelm. Lekta ends her article: “It’s not enough to describe Jäderlund’s poems as craft–they are magical.” That is to say, Leka’s response is much like Jäderlund’s response to Celan and Bachmann. Out of the older poets’ correspondence, she sets off an infectious chain of mimesis that involve readers and writers on a bodily level.

Anne Carson has suggested that we read Celan’s work as if always already in translation. The same can be said about Jäderlund. While poetry in translation is often criticized for enacting a loss of the original impact of the poem, both of these poets are incredible examples of how poetry in translation–in deformation–do not need to equate with loss, but can be events, moments of transformation.