This is a poem about a hospital. I wrote it in the presence of that hospital. It was important for me to put my body into relation with the building. To move around it. To measure the building against the scale of my own seeing. So, I went to Mobile with my iPhone and my notebook and I took a lot of notes. I don’t remember how I arrived—or I remember shards of the journey. I rode on the Greyhound for a long time, in silence, the highway lifted out of brackish water on a causeway—to protect it from the damage that water can do to concrete and asphalt, churning, grinding, returning. I was a stranger in this place and each thing seemed unbearably hot and bright. None of this is present in the poem. Not the Greyhound, not the Lyft I took from my hotel in downtown Mobile, not the long walk across the hospital grounds, deep green of its lawn stretching out beneath the concrete drums of the hospital. Impossibly thin and impossibly ponderous: the structure that my body needed, needed to measure against itself. None of this is in the poem. The poem is its absence. I mean, you could think of a poem as a perforated thing, a punctured thing—through which the vast specificity of the world drains.

at least you’ll die in an air-conditioned bed, brace of plump pillows to caress your neck,

The hospital in question was designed by the architect Bertrand Goldberg. If you’ve heard about him, you’re probably from Chicago. He designed Marina City—the iconic corncob towers on the Chicago River. He imagined—and tried to enact—an architecture that would have the complexity, the density, the difference, of the city itself. His buildings swell, distend, incorporate estranged institutions: steak house, theater, apartment block. He believed that radical architecture could make the world better: more porous, more democratic. That turns out to be a sad thing to believe in the 20th century. Now his name is in danger—of disappearing from the record of what architecture could be. His buildings are, for the most part, neglected. Some have been demolished. The rest are remodeled, repainted. People seem allergic to them, their strangeness, their beauty. The way they promise to capsize the world in which they stand.

as you were born caressed, never a day w/out love.

By the time I wrote this poem, I had seen a lot of Goldberg buildings. I would fly to Phoenix or Tacoma and walk around a building, taking pictures of it with my phones writing notes in my notebook. It was a way of opening up my poems. The world, the world in which these buildings stand or decay—that world might seep into the poems, staining them, changing them. I sought that out, I solicited it. I wanted my poems to be corrupted, to belong to the world as much as they belonged to me.

Why then does loss pursue you. Be still, be calm, at least it’s almost done.

I am aware of the irony. I think Goldberg was too. People do not (generally) go to the hospital to have an aesthetic experience. What if we did? What if the spaces of dying and birthing, healing and enduring, were as beautiful as cathedrals, as monumental, as beloved? What if we tended the actual bodies of the living with the same care we offer to the imaginary bodies of the gods? Being in relation with these hospitals, you find yourself asking questions like that.

Lady you lunch in the shadow of the megabus, your life will not be saved.

Being with these buildings, studying them, touching the rough grains of the concrete—it changes something. I learned a new way of seeing. Surfaces stopped receding. I saw the textures, the way that buildings were made. I started looking at architecture, rather than through it. This is one thing poetry can do for you: it can teach you to look at the world again.

Have you lost much? Not much. (Not true).

This is one thing poetry can do for you: it can make itself impossible. I think sometimes about the old joke: writing about music is like tapdancing about architecture. There is, the joke admits, something unsayable about architecture, something that resists being translated into the idiom of the body. That resistance is, I think, where poetry happens. Poetry is the language of what otherwise cannot be said.

Now every afternoon is as implausible as love. Beside you at the bar a grown woman weeps into her (second?) martini.

And you do use your body. Don’t you use your body to encounter the limit of what can be said? A kind of dancing, let’s call it, the way you step toward it, then step away.

draped structure / comes to ground / abstract and / poetic interface

What do you do with architecture once you start looking at it? In the books I’ve written about architecture over the past ten years—Discipline Park, my book about Goldberg, is the first of three such books—I keep encountering this problem. How do you translate architectural aesthetics into poetic form? This is not a question that has an answer, really. Rather, it is one of those insoluble problems which electrifies the air around it. And the poem begins to shiver in response.

how careless is memory, variable media, variable dimensions.

Goldberg’s buildings take a simple gesture and repeat it. An arc, a curve of concrete: it repeats, turns, returns. The building ripples as your body moves around it. It seems more complicated than it is. Only when you look at a blueprint—or a photograph—do you recognize the simplicity, the clarity of the design. He rewards you for coming to the building, presenting yourself to it; he gives you more beauty than you expect (deserve). That’s something architecture could do. It could reward you for being a body.

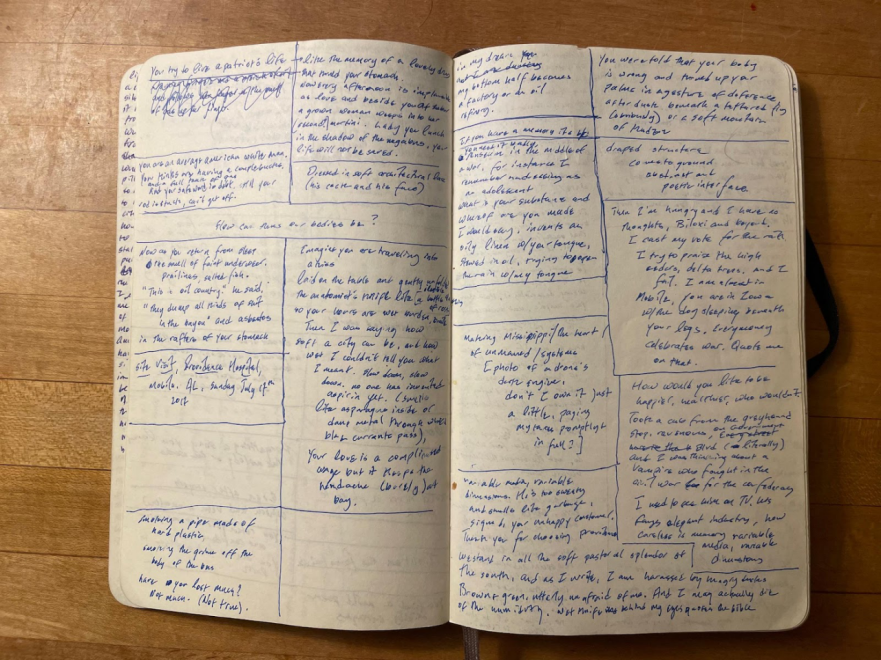

after dusk beneath a tattered flag (obviously)

That’s something a poem could do. It could make a simple gesture and repeat it. It could transform the page into a plat, a site plan. It could create narrow piers of text, so that it seems impossible for the poem to carry its own weight. In my notebooks from the time, text gathers in strange, oblong rectangles. There is no hierarchy, no clear order. It is hard to tell how to read, where the eye should travel. Are you looking at prose or verse? How much of a poem’s architecture do you need? All of it, actually.

Notes from my trip to Providence Hospital in July, 2017

I am quoting here from my notes, notes I took while I was in relation with the building. I am quoting fragments of saying and seeing. These fragments, these notes—they are travelers, strangers. They rose from some place. Somewhere among these fragments I wrote a poem. A poem about a hospital. A hospital in a strange city, a city whose name suggests that it is permanently in motion.

Cafeterias w/slovenly guacamole. I am, at least, intolerable even to myself.

None of the fragments I quote here are part of the poem I wrote. At some point, they fell out of the poem. Loose change, lost receipts. Editing, we tell our students, is about finding the poem’s form. It is a process of loss: a process in which we impose loss upon ourselves, giving up some of what the poem could be to discover what it is.

Or maybe it’s just the weather, banks of thunder that press the air and the crickets singing at the gloom.

None of the fragments I quote here are part of the poem I wrote. Or all of them are. You might think of them like the rests in a piece of music. A structuring absence, a pulse of silence. Which makes the melody possible. You might think of the poet as a gleaner, a gatherer, who goes about collecting such moments of silence.