We’d like to believe that our sense of taste, obscure to us, makes no assumptions at all. I grew up an Indian expat’s son in Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, a small proud landlocked Southern African nation, population 7 million. (Trump may have been half-mentioning it when he said “Nambia”.) Zambian, Pan-African, and Indian nationalism of a particular, optimistic moment in the 70s and 80s shaped me in ways I feel powerless to undo. At the same time poetry has always intrigued and touched me in secret places. I’d written my first poem in third grade, I think, with my mother’s help, and I’d written another a couple of years later—my first memory of rapture in the act of writing—but then I’d gone silent. I hadn’t yet heard about the Indian who won the Booker, so writing didn’t seem like a glamorous profession. Poetry writing, especially, didn’t seem like a reasonable occupation at all, not like engineering or even the natural sciences. In that age of the Third World technocrat, the humanities as a whole were for students who got low marks. When, at the age of 15, I was touched again by Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” it actually frightened me, as if I were being called by ghosts and ancestors down an unwise path. I gingerly started getting into some of the Americans and the moderns but it seemed almost obvious that people like me didn’t become poets.

Then two anthologies happened. One was Saleem Peeradina’s Contemporary Indian Poetry in English (1972), which I quietly stole from my sister’s almirah. The other was Wole Soyinka’s Poems of Black Africa (1975), my first ever poetry purchase, in a nondescript strip mall in Gabarone, Botswana, sometime in the late 80s. Like it or not, I felt instantly close to these two books in a way that I had not yet to anything in the canonical Anglo/American tradition. They gave me all kinds of permissions—though I would not have been able to articulate it in this way then—and importantly, they eventually showed me routes back into European and world modernism.

Soyinka’s anthology was one of the few poetry titles in Heinemann’s legendary African Writers Series, and thinking of it now, I am struck again by how anthology-making can be a kind of heroic task. It must have been impossible. He dared to bring together poems from a number of Africa’s languages, above all bridging the Anglophone, Francophone and Lusophone, making a measure of quality and insisting on it, mediating translations; a task that, sadly, I don’t think has even been attempted since. The burnished orange cover of that book is emblazoned on my mind’s screen, and too the names of at least a few authors in its particular italic font: Dennis Brutus, Okot p’Bitek, Bernard Dadié, and perhaps above all, Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo (1901-37).

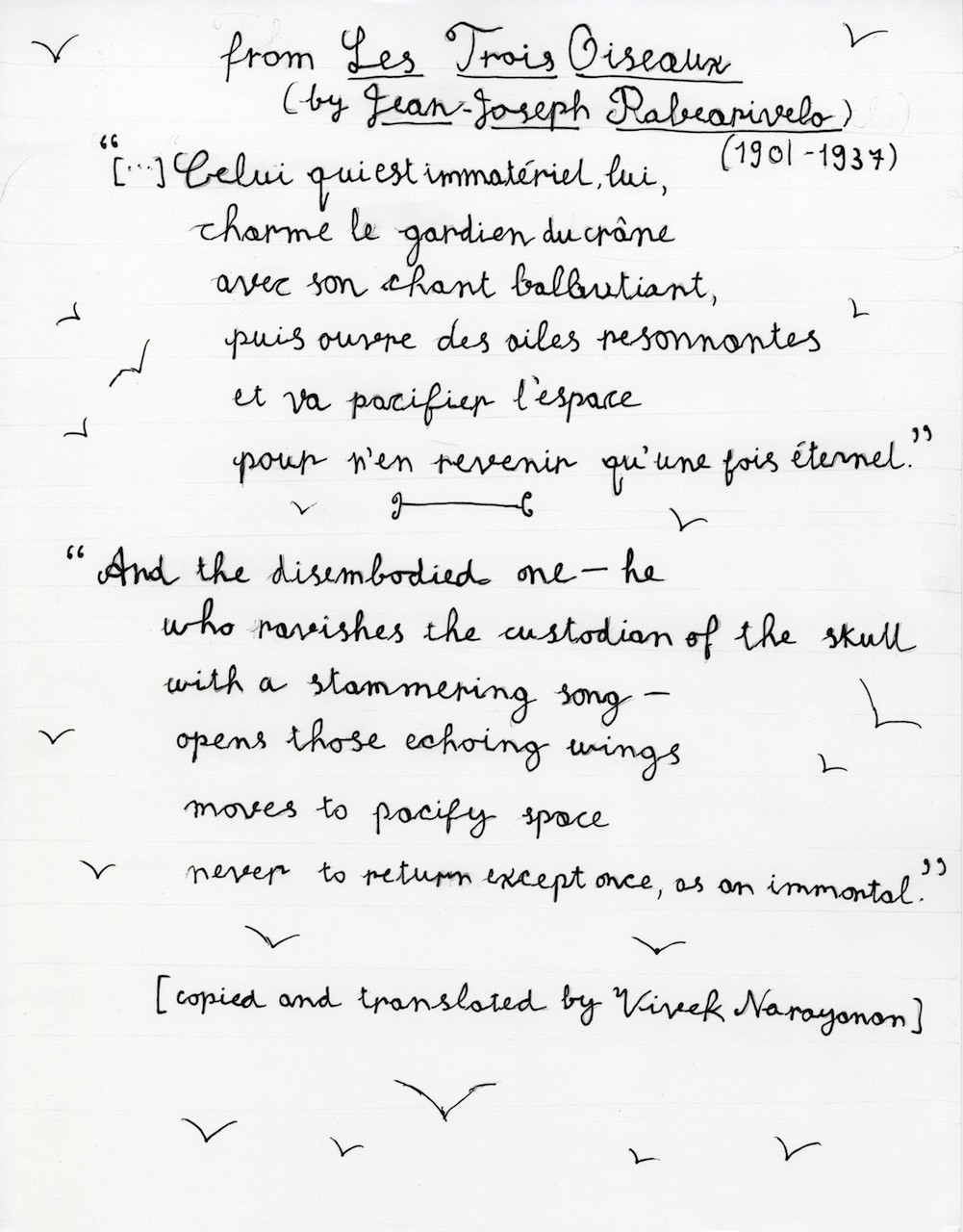

Rabearivelo is today believed to be Africa’s first modernist poet, though that ought to be a claim that requires much more long, still-to-be-done wide excavations in African modernism. In any case, he was a key acknowledged influence on Senghor and the poets of Negritude. According to Jacques Rabemanjara, Rabearivelo’s disciple, and Leonard Fox, Rabearivelo’s most extensive translator, Rabearivelo first published three books that showed a “mastery of language, [and an] extraordinary skill with French prosody,” but it was in the book from which “Les Trois Oiseaux” is taken, Presque-Songes (Near-Dreams) that he truly came into his own. By the poet’s notebook, these seem to have been written almost simultaneously in French and Malagasy, in facing columns, sometimes one first, sometimes the other. Rabearivelo’s next book was called Traduit de la Nuit (Translations from the Night); and his work clearly shows us how so-called surrealism can emerge independently from a kind of translation, in his case, from the old songs and thinking of the Imerina kingdom. His stock has risen slowly, too slowly for my taste. For years it seemed like there wasn’t that much of him, but his Oeuvres complètes in two volumes appeared in 2012, showing him to be an extensive writer running into thousands of pages not just of poetry but plays and fiction too. Rabearivelo also kept up an energetic correspondence with French writers, had kilos of books regularly shipped to his island to keep himself current, and longed to be admitted to the scenes he circled like a distant satellite. They say he committed suicide at the age of 37 after the death of his favourite daughter, and after his application to attend the 1937 Exposition Universelle in Paris was denied by the French government in favour of a group of Malagasy basket weavers.

I’m to discuss his poems with a new batch of students this semester. In “Les Trois Oiseaux,” the symbolism of the first two birds seems more or less clear, it’s the last one that always keeps us thinking. A part of me can’t help feeling the third bird is surely Rabearivelo himself, with his stammering song and his undeniable immortality.