Summer was closing, and he moved through the last of it,

finding a park with fairground music

coming from somewhere behind the trees.

Walking round, he understood that the funfair

is nothing to do with cork-shoots or coconut shies,

the carousel, the booster or the bumper rides,

not balloons-and-darts, not the cotton-candy,

ice-cream, salt water taffy or fries—it’s fear,

it’s the high-wheel of fortune and despair: that

thin glimpse of joy and freedom, before

rattling back to earth, loose-legged and spinning.The real carnival is the other side—

beyond the midway, the concession stands, ‘Hot dogs

a nickel, three for a dime’, the merry-go-round

with its lights and bobbing horses, the churning calliope,

shouts, screams, sprays of laughter, gimcracks, baubles,

stuffed animals, those feather-headed

Kewpie dolls on sticks,

the children crying out, the barkers calling.

Follow the lights:

the colored electric bulbs strung up

on spitting wires, the smell of burning fat and engine oil,

cheap perfume, sweat and food and dung.

Here are the pinheads, the half-boys, the lobster-boys,

snake-men, midgets; the cage

and the geek inside, the man with the horrors,

waiting to eat the heads off chickens

for a bed of wet straw and a pint of rye.This is not the worst.

The worst is the hall of mirrors

where you catch sight of yourself, twisted,

swollen, unrecognizable.

Then a beautiful woman—your wife, your lover.

Then it’s you again: old, crippled;

her as a turning witch, you as the held man.

And you blow every piece of your glass apart.

It’s the worst thing in the world,

catching sight of yourself.The next day, the carnival is gone.

All that’s left is the flattened grass

and trodden ground,

the litter of popcorn boxes,

Dixie cups and empty bottles.

It looks like the place

where some huge, fantastic beast had foraged

and lain for a while

before moving on.

1951 (excerpt)

Feature Date

- April 19, 2018

Series

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

Copyright © 2018 by Robin Robertson

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission

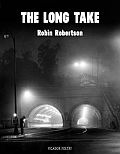

Robin Robertson was brought up on the north-east coast of Scotland and now lives in London. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, he has published five collections of poetry and has received a number of honors, including the Petrarca-Preis, the E. M. Forster Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and all three Forward Prizes. His selected poems, Sailing the Forest, was published in 2014. The Long Take will be published in the U.S. by Knopf next January.

A noir narrative written with the intensity and power of poetry, The Long Take is one of the most remarkable – and unclassifiable – books of recent years. Walker is a D-Day veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder; he can’t return home to rural Nova Scotia, and looks instead to the city for freedom, anonymity and repair. As he moves from New York to Los Angeles and San Francisco we witness a crucial period of fracture in American history, one that also allowed film noir to flourish. The Dream had gone sour but – as those dark, classic movies made clear – the country needed outsiders to study and dramatise its new anxieties.

Watching beauty and disintegration through the lens of the film camera and the eye of the poet, The Long Take is a work of thrilling originality.

“A bullet of a book. It is deeply noir, scything open post-war Los Angeles to show us a living, breathing city… It is a book that hits its target. It flies. It feels true.”

Ryan Gattis

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.