When David asks, “Where does the saying ‘She still hasher marbles’ come from?” I’d been talking about my ma,who’s 94, same as David, though David said,“I’m 94 and four months, so she’s still a child.”I say, “It’s got to come from being a kid, wouldn’t you think,and playing marbles?” “Yes,” he says, “it probably must.But Tom, do kids even play marbles anymore?”Earlier, he’d said, “I live in a place called Brook Haven,but we all call it The Death Camp. There are some nice peoplewho live in The Death Camp, people I’ve known a long timewho have a sense of humor, or try to have one,about their situation, but the problem is the horizonis foreshortened, if you know what I mean . . .”Then David says, “You know there’s that poem aboutthe two shepherds who sing verses out of Virgiland the moment one of them finishes, the other says,‘That’s just fantastic, it’s wonderful!’ and the shepherdsseem like they love one another because the other onestarts singing different lines of Virgil and whenhe finishes his friend says, ‘That’s just fantastic,it’s wonderful!’ and of course, it’s Virgil pullingall the strings, the shepherds are Virgil acting likeshepherds who are quoting Virgil whom they love.I saw Arthur’s widow, Marie-Claire, to show hera book in which Arthur’s and my poems had been translatedinto French and she was gracious and enthusiasticas always, but then she asked me if I’d ever beento visit her in this apartment where I’d beento see them lots, so even though she wasn’t sureof exactly who I was, at least she knew enough to knowthat I was somebody she was supposed to be fond of—but by how she kept smiling at me, she was anxiousfor us both to act like she knew me.” “So she sort of knew whoyou were,” I said. But David, who has no truck withthe pathos of old age even as he feels it, didn’t answer.Outside my window were seagulls coasting and beingbuffeted above the whitecaps in a bright glarethat was hard to stare into. We were coming to the endof what we were saying, and now obligatory emotionswhich we nonetheless honored gave our sayinggoodbye an artificial quality, a forcedheartiness of affection until David quotedfrom a poem, not his, referring to the Sphinx’s beard,“It’s in the cellar of the British Museumwhere the Athenians lost their marbles,”and then David said, “Much love,” and we wereoff the phone and I stored his numberin my Contacts and erased the two 617numbers for the 857 number and wonderedwhat he’d say if he knew that someone had madea virtual-reality app of Bergen-Belsenand that the next step is to make it “more tailoredand personalized for visitors.” One other thing David said:“All my new poems ask questions like, ‘Who is this whowho is saying this and what, anyway, is the this?

Conversation

Feature Date

- August 30, 2022

Series

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

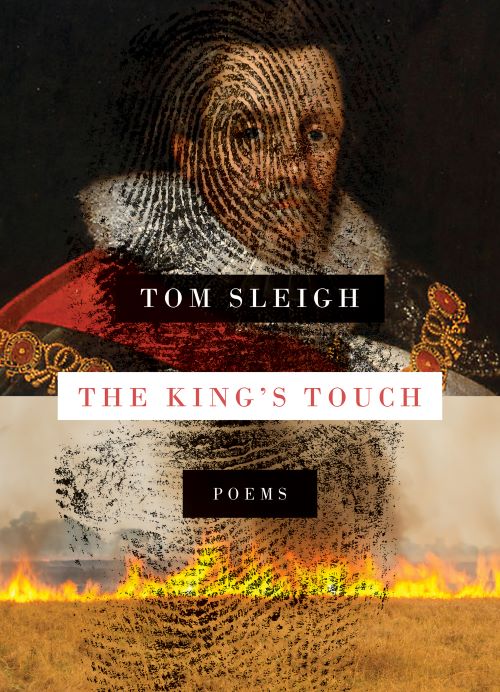

“Conversation” from The King’s Touch.

Copyright © 2022 by Tom Sleigh.

Used with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

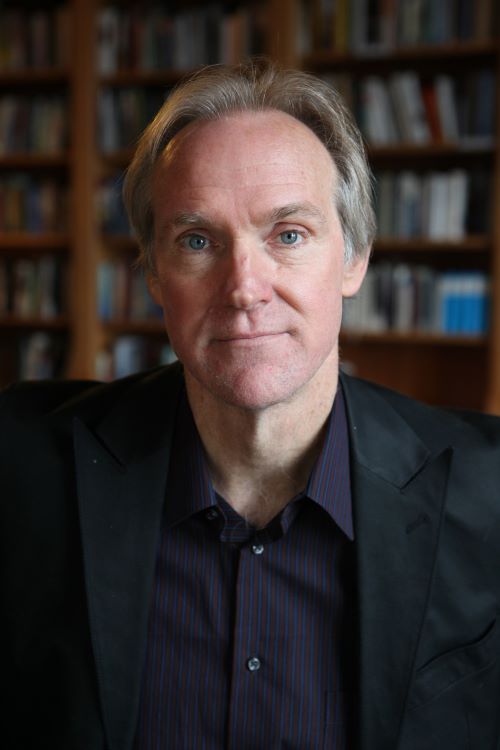

Tom Sleigh is the author of ten previous poetry collections, including House of Fact, House of Ruin; Station Zed; Army Cats, winner of the John Updike Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters; and Space Walk, winner of

the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. He is also the author of two essay collections, The Land between Two Rivers: Writing in an Age of Refugees and Interview with a Ghost. Sleigh teaches at Hunter College and lives in New York.

“Tom Sleigh's poetry is hard-earned and well-founded. I greatly admire the way it refuses to cut emotional corners and yet achieves a sense of lyric absolution.”

—Seamus Heaney

“Generous, meticulous, haunted and grounded, The King’s Touch handles contemporary life with alertness and compassion for a world in which ‘A Man Plays Debussy for a Blind, Eighty-Four-Year-Old Female Elephant’ while friends kill themselves and voices urge, ‘You’re better off dead, you useless piece of shit.’ The piano player ‘shuts his eyes and leans his forehead against hers,’ Sleigh imagines; ‘it’s like each one’s/listening to what the other one’s thinking.’ Sleigh’s business, like Dickinson’s, is circumference; though he can’t erase the voices that drive individuals and nations mad, they can be subsumed in music. Reading The King’s Touch is an extraordinary pleasure not to be missed. ”

— Joyce Peseroff, Arrowsmith Press

“Sleigh’s deft hand, attention to detail, and literary experience make him an ideal interlocutor. . . . In The King’s Touch, Sleigh excels at seeing and interpreting the world as it is, on its own merits.”

—Kevin O’Rourke, Michigan Quarterly Review

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.