With him pressed so close beside her,she couldn’t sleep. Perhaps it was his skin,or the rain. It kept raining.She lay there trying to rememberexactly how many thoughts she could have.Was it 30,000 or 70,000? Per hour?Or was it per minute?She’d heard from someonewho’d heard from someonewho heard the number, whatever it was,from an HVAC specialist.She placed his hand back on her chestwhile another fifty thoughts leaked out.They’d both been reading César Aira,who said that for every sentence you writethere are many implicit questions.She was surprised to find herself still wearingthe shirt he’d pulled down from the neckto reach the rest of her. The shirtwas like a second skin, color of her nipples.Pale burgundy. It held her together,kept her from flying right out of her body.His T-shirt had a hole, a tear near the hem,which she only later remembered noticing.Fingering.How many other thoughts had she hadwhile her body was responding like that?She didn’t know if pleasure counted as thought,or were they separate categories.The smell of someone lingered.Or was it cilantro? The insolesof the red shoes in her bedroom?Secondhand. They were like ballet shoesthough she was not a dancer.The fact of the shoes elicits hundredsor thousands of thoughts,and if she could just keep writingat top speed she’d be able to count them.She can type 120 words a minute,and let’s say a thought averages fifteen words:she could type approximately 480 thoughts every hour.With a pen she writes more slowly.To whom is she writing?Over a small glass of whiskey she’d askedwhat was the most debauched he’d ever been.“Dropping acid with a friend,” he said.She didn’t tell him about lying on the floorhalf-naked with the red ballet shoes beside herin an apartment not far from the Sacré-Cœurthe night someone drove a truck at high speeddown the crowded sidewalk.Those shoes—those thoughts—How quickly they moveacross the 90,000 miles of neuronspacked into her head. How longhad the shoes been worn by someone elsebefore she wore them?Isn’t there something morbid about that?Or is it like taking psilocybin,you realize everyone is connected,the living and the dead?Even if it all ends tomorrow,she’ll have been grateful he awakened her.She’d come to expect a life without much pleasureother than rain and sleep and solitudeand whatever she could make in her notebookand in the narrow galley kitchen buffeted by cabinetsfilled with glass jars and oils and a canister of propanein case of emergency.The overhead light has been out for years.Why? Why can’t she climb the ladder,unscrew the bulbs, fix the wiring?She found him sitting quietly at the kitchen tablewhere she could smell the basil she’d watchedhim tear into small pieces the night before:basil and sun and man: and then she wipeda few grains of coffee from the counterinto the other irreducible qualia of morning.

Critique of Pure Reason

Feature Date

- May 5, 2024

Series

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

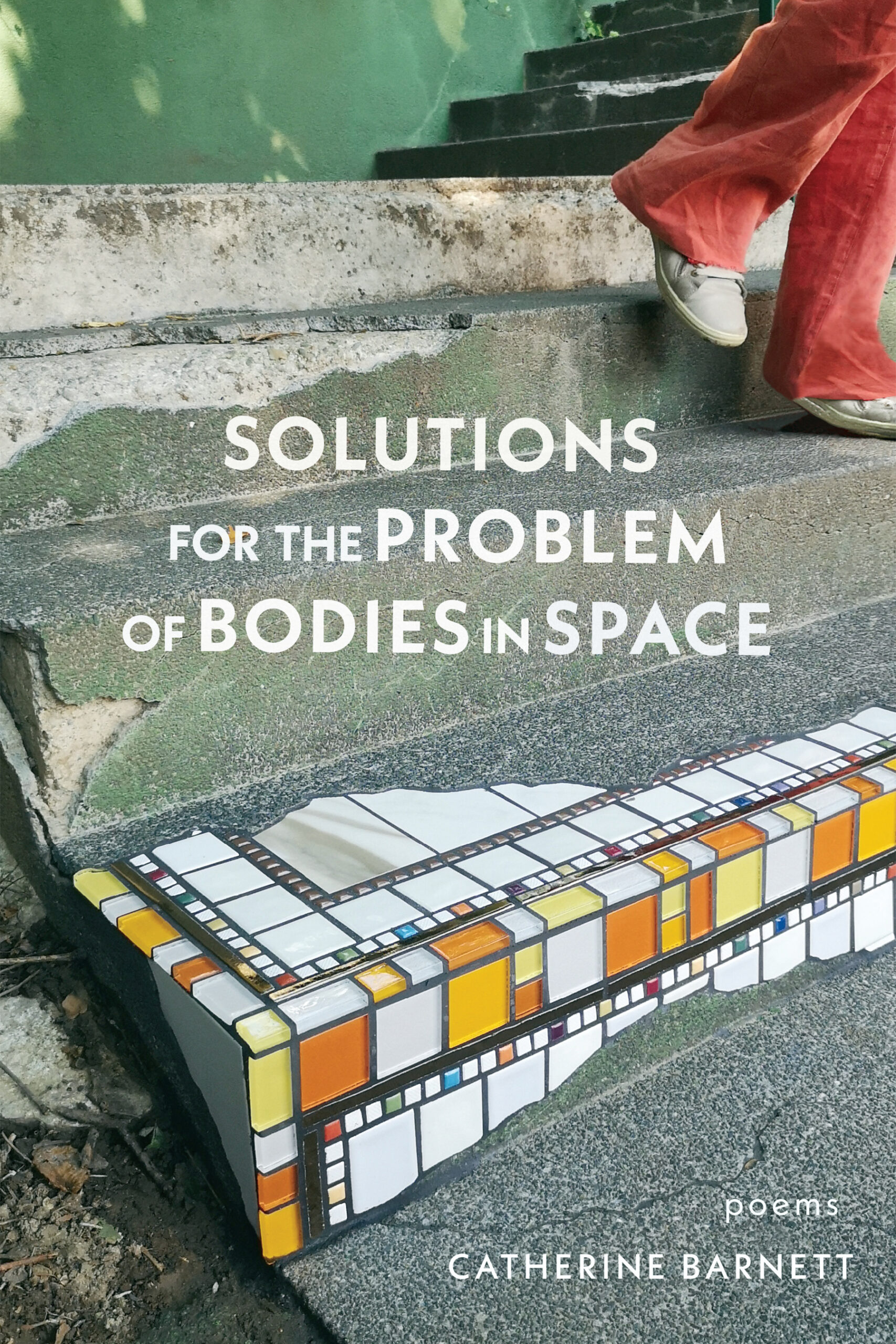

“Critique of Pure Reason” from Solutions for the Problem of Bodies in Space.

Copyright © 2024 by Catherine Barnett.

Used with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org

Minneapolis, Minnesota

“The poems in Solutions for the Problem of Bodies in Space unfold in the company of loneliness, an experience I, too—like the mind at work here—have needed, dreaded, and craved. As attuned to humor as to sorrow, Catherine Barnett finds comfort, story, and the metaphysical in objects I might otherwise not have noticed—buttons on a father’s jacket, a moth pressed against a window at night. These images are vivid reminders to pay attention, and in these poems, attention leads to memory, to the California hills, to a blue whale suspended overhead. To a village of dolls, a coyote in the cemetery. To elegies so deeply felt and clearly articulated you can almost touch the loss pressed into the dirt where hyacinths grow. ‘What is metaphor for?’ a daughter asks. ‘For you, my father, / genius in a big dumb object.’ Taken together, these meditations make a case for love even when they talk of failures of love; even when things (and lives) are beyond repair, they make a case for repair. In this ‘hive of enigmas,’ time flows through faucets and ‘there was no reason not to be alarmed.’ Like the nucleus of something I have no name for, these poems are charged, unpredictable, exquisite.”

—Dianne Wiest

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.