iv.

You ride the elevator to the eleventh floor of a hotel

the tallest in our seaside town

pale yellow or coral or white

no lighthouse but an abrasive plinth

chartered to the shore by cement.

Holy fathers, beatified men their bronze or wooden statues dot the coast

from San Diego to San Francisco

Up El Camino Real—

where curved poles topped by soundless bells

hang like sickles.

A river, a mission, a chapel, its garden.

An ocean, a boardwalk, mountains, a freeway.

The town’s Franciscan priest,

Junípero Serra, once had his hands

doused with red paint. Genocidal

churches, arable lands. A museum

with pieces of or whole Chumash

bowls and other poorly-handled things.

School children appraise them. It is an annual ritual.

*

You request a room overlooking the Pacific.

The elevator does not stop; the hotel is never full.

A wooden pier—once of remarkable length—

extends towards the Channel Islands,

draped in fog, reachable by boat

if you wake with the fishermen before dawn.

A novel was set in those islands about the sole

inhabitant of San Nicolas. The facts are:

a native woman alone for eighteen years

spotted on the beach skinning a seal;

hauled ashore to the mission where dysentery

killed her and her language off. She was given

a Christian name. We read it in school

but remember nothing except

the word Aleutian and a numbness

sharpened by no response. It was written

by a descendent of Sir Walter Scott.

Scott was, among other things, an early translator

of Goethe. Dear sister. What you have learned is a dying craft.

The elevator opens onto a quiver of directions.

*

You drift back to a rose garden, a small women’s college

where each girl is permitted to pick and take

all the roses she can carry back to her room.

*

The pier, battered by storms, is rebuilt. A catafalque

decked in American flags from sternum to navel.

From this angle, the sea is a parade of elbow length satin.

Excavating the cave of the lone woman at San Nicolas,

diggers were halted by the Navy. It lies half-dug,

disputed, full of sand, making distress calls.

You run towards the end of the pier with your arms

open, lodging in its sights like a gale or target.

*

The room’s ceiling is shot white powder,

liable to yellow and stain.

Someone later recalled seeing you taking

in the view from your balcony.

The sun is flattening into the sea and below

there are families fishing or striding

in the dimming orange light. It is well-beyond

happy hour in the tiki-themed bar,

the seafood restaurant we thought was so sophisticated.

There’s a revolving ballroom,

long since closed, where high schools held their proms.

Corsages, rented limos, hairspray,

saliva drying on gums in windy sunroofs. The sun

is a gold disc over the grey-blue waters of the Pacific.

*

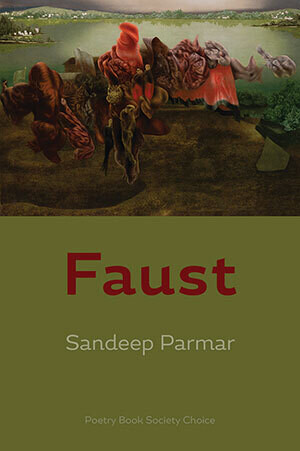

To strive, you think, to know. You’ve brought with you a copy of Faust. What is it to want to know everything. The light sharpens to a point to a full stop to an ingot of gold at 7.30 p.m. This alchemy. Do you open Faust. Do you leave it in the dingy room, on the beige bedspread, a wager of its own in our Eden this Arcadia. Faust’s strip of coastline, a paradise built in his dotage, unbegun but in his imagination, an inner light. Now you remember everything. You are in a state of sudden alertness. You find your aim you strive. There is the sun, blinding all the summer day. There is the cli0, where Euphorion dropped into blackness marching heroic. You think of the roses and how you carried them all in your arms. Striding full of hope into another century. To want, to owe, to feel shame. Dear sister. To wish to know everything Faust says you must become nothing Mephistopheles says to extend beyond what is human you must become the Spirit of Eternal Negation Faust says you must be willing to die but I am not afraid to die Mephistopheles says I will route your indentured soul from an eye an ear a navel a fingernail for the jaws of hell are always open Faust love has waded through my many dreams and orchestrations Mephistopheles opines we were all girls in another century baring our arms in an inhabited garden Care slips through the keyhole like smoke a kind of being without a kind of alchemy Faust you will never fall where love can be seen from a great height rising above these hills like a memorable star.