IDEAS around the Brocken and hearts around mountCalvary235Some are the color of daysOthers are a blood red hazeOf your blood I had drunk half a decanterI threw the other half upon the waterFrom it was born a great vesselAn acrobat in green aglitterUpon the end of the mast furthest aftAll of the dead groaned in the form of wavesAnd the damned stretched out their backs’ black rocksCries of the living twisted in seaweedThe horrible gleeful, the sad more horribleIn the hold like the prisons in ’93236Exhaustions, performing dogs, officersAnd wily mournful women.The fateful sound of waves in the marginsAnd on the boat humanity played cardsA minister of state read his fortune thereFurthest aft.Why all the blood spilled at CalvaryFor this ship mounting the waves of the dead?There must be suffering for there must be life and visionThe red bloodstain reached even to the rocksEverything was quivering, my lyre as well,And the vessel carried all of humanityAs for me, I know a boutique tinted with the blood of the LordBut the frenetic “successor”Has a flag put there in the same colorThe sky today is red with Christ’s red bloodYet upon me, trembling against a marble vaseIn the flowery Luxembourg gardenThe wild boar that left the treesHas thrown his golden tusks and his furyTomorrow the nasturtiums will have witheredAnd I will see, Lord, how you are murdered.The northern air has scarred over the wounds.

Glass of Blood

For Juan Gris234

Feature Date

- May 20, 2023

Series

- Translation

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

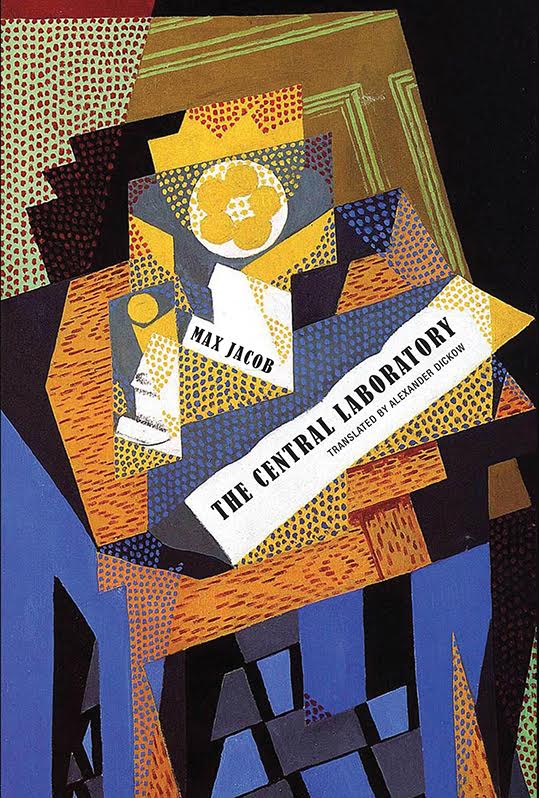

“Glass of Blood” from THE CENTRAL LABORATORY: by Max Jacob.

Published by Wakefield Press in July 2022.

English Copyright © 2022 by Alexander Dickow.

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

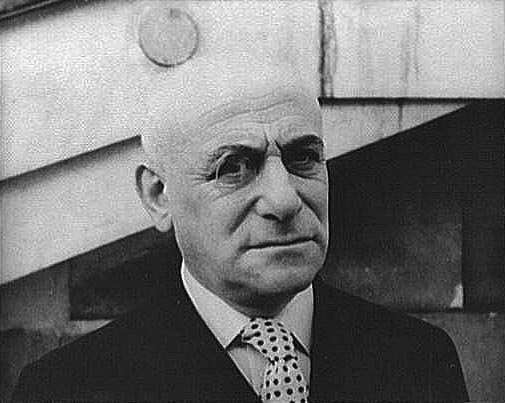

Max Jacob (1876–1944) was a French poet, painter, writer, and critic. A key figure of the bohemian setting of Montmartre Paris and the legendary cubist era, he rubbed shoulders with such figures as Guillaume Apollinaire and Amadeo Modigliani, was a lifelong friend to Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, and Jean Cocteau, and an influence for a generation of young writers. After experiencing a mystic vision in his studio apartment in 1909, Jacob converted from Judaism to Christianity in 1915, with Picasso as godfather. Arrested by the Gestapo in 1944, he subsequently died in a deportation camp from bronchial pneumonia.

Alexander Dickow is a poet who writes in French and English. His books of poetry in English include Appetites (MadHat Press, 2018) and Trial Balloons (Corrupt Press, 2012). Caramboles (Argol Editions, 2008) is in both languages. He has published full-length translations of works by Henri Droguet, Sylvie Kandé, Max Jacob, as well as Gustave Roud in a cotranslation with Sean T. Reynolds. He is currently at work on a diptych of narrative/dramatic poems under the general title Hob’s Labor, parts of which have appeared in New American Writing, This Broken Shore, Snow, and The Fortnightly Review. Dickow is professor of French at Virginia Tech.

When Max Jacob published The Central Laboratory in 1921, Cubism’s glory days had passed, the Parisian Dada movement had just officially come to an end, and the surrealist movement was yet to be born. The poetic scene in Paris was between definitions, and in that sense, Jacob’s work embodied the moment.

The Central Laboratory is distinctly modern yet utterly discordant with anything else that had been published before: a grab bag of popular genres, operettas, Breton folk song, nonsense poetry, nursery rhyme, cockeyed doggerel, pastiche, parody, and puns in which sound often trumps sense. In this collection, Jacob changes register on a dime, shifting from societal sarcasm to mystical sincerity, bearing allegiance to no school or form but his own. Employing the symbolist method of obscure reference, the cubist fracturing of perspective, Dadaist discontinuity, and a dream logic that was at stylistic antipodes with what surrealism would soon become, Jacob drew from almost twenty years of work to assemble an array of “stoppered phials” in this tongue-in-cheek laboratory, each one of them carefully mislabeled. It most clearly presents what Jacob described as his “art of disappointment”: the sabotage of readerly expectations in which doubt and disorientation serve as poetic principle, and the traditional jilted lover and jilted poet join forces to propagate a new form of jilted reader. Mixed signals, mysterious rationales, and mocked allegory formulate a camp sensibility, a “queering” of literary style that is as riddled with contradiction as Jacob himself had been in his lifetime.

The book remains, a century after its initial publication in French, utterly peculiar and for too long lost in the shadow of Jacob’s more famous poetical colleague, Guillaume Apollinaire, as well as the one cast by Jacob’s own earlier, more famous book of prose poems, The Dice Cup. Jacob himself said of The Central Laboratory: “it sums up twenty years and reflects twenty states of soul, often twenty styles either suffered or created by me.”

“Jacob moves freely between sense and nonsense, beautifying the confusing, and at times, he delights in nothing less than the joy of how words sound.”

—Patrick James Dunagan, Rain Taxi

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.