Not with lust,though the unsettled lover that carries my childthrough woods of tapped maple treeslaid the sum of her muscular body on top of mine last nightand I wondered what could be made of that feeling,already one hand on my belly holding the two of themwarm, deep in snow and the slow drip of sap into each pail.We’re walking with the biologist from Toulousewhose burly husband fires up the sugar shack while their two sonstrail behind, and I stay at her side, wanting the closenessof another mother. It’s too early to know which heartis viable, or how I will explain the singular lifeI’ve chosen, with each step cautious not to fall on the ice-rooted path, I hold onto anything within reach—the blunt lightof sky, her arm, the lover, my child, trunk of the hardwood—I wantto open my mouth and taste what there is.No view of the mountains,only a matter of time. But this is wherewe would admire things like eminence, panorama,perspective, or note the way our bodies are madeexpansive by the intimacy of strangers who see us. What other waydo we know we are home? The scienceof existence directs us to a language of outcomes. If this,then this. I’ve read about the generosityof trees, especially the mothers, ancient and wise, that nurtureand grieve and perceive each bodythat passes through. Silhouette, shadow. And here we are takingwhat we can for our own sweet pleasure.At the clinic, the doctor named the risk factors,and when it was over, praised his collectionof eggs. I was still nothingmore than a repository of longing, I was no one’s passion, helddown by other forces. And months later, I watched the filmof my uterus on the screen—all I had to dowas lie there while two embryos were releasedinto the dark of meuntil the lights went out, and I was infinitely alone,only the nurse’s hand to hold.What part of thisis luck? What part of luckcontains happiness? What partof happiness is the fact of our interdependence?Of desire is science. Of taste is feeling. Of instinctis love. Of child is poetry.There’s no need to apologize for the clouds.Do you want to discuss reduction? the doctor asked me.And to think of the frailty of treeswhen other trees are removed. The sentienceof the forest, alive yet mute.That I could choose to eliminate oneand keep the other. That something was taking format the boiling point, and all I could dowas open my mouth to the pure amber light echoingfrom the place where the mountainsshould have been, sticky and solicitous and eager.

How My Children Were Made

Feature Date

- July 18, 2024

Series

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

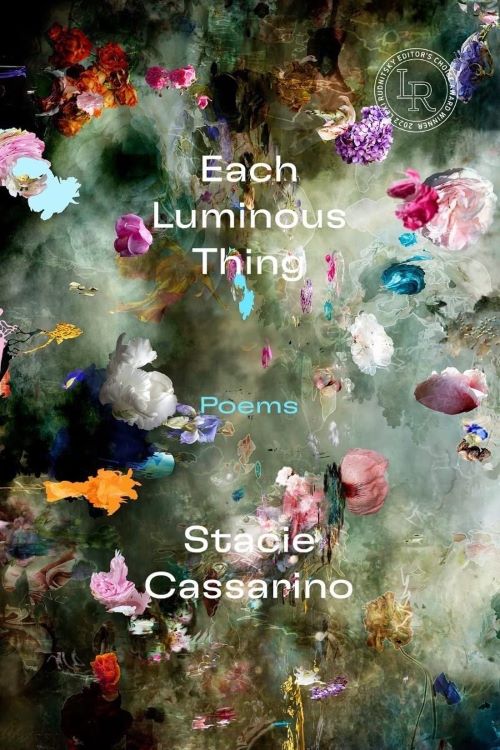

“How My Children Were Made” from EACH LUMINOUS THING: by Stacie Cassarino.

Published by Persea Books on November 7, 2023.

Copyright © 2023 by Stacie Cassarino.

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

Stacie Cassarino’s recent collection, Each Luminous Thing (2023) won the Lexi Rudnitsky Editor’s Choice Award and was recommended by the New York Times Book Review and the Washington Post Book Club. She is the author of Zero at the Bone (2009), which received a Lambda Literary Award and the Audre Lorde Award, and a scholarly monograph, Culinary Poetics and Edible Images in Twentieth-Century American Literature (2018). She is a recipient of the 92NY “Discovery”/The Nation prize. She lives in Vermont with her three daughters.

Winner of the 2022 Lexi Rudnitsky Editor’s Choice Award

From the boreal woods of Vermont to the coastal canyons of Southern California, Stacie Cassarino’s highly anticipated second collection of poetry maps the parallel tracks of walking through shifting terrains and becoming a mother. Cassarino patiently explores the physical cadences of landscapes as they are superimposed with internal and linguistic navigations of desire, longing, loss, and love. Stepping into the natural world with a lens on earthly objects encountered through the seasons, Cassarino holds both sorrow and praise for their ephemerality, and for the fragility of human connection, and in doing so reconciles her own sense of home. These are quiet, resilient poems, reflective of the urgent grasp to preserve and fill the silences that live around and within us; they affirm the presence of beauty through solid facets of nature and through the enthralled body that announces its love, even as things come in and out of focus.

“Zero at the Bone contended with loneliness and longing—for love, for belonging, the (im)possibilities of erotic intimacy—and these preoccupations carry over into Each Luminous Thing with fresh urgency as the speaker falls into helpless and seismic unconditional love with the three daughters whom she must protect and nurture as best she can.”

—Lisa Russ Spaar, The Adroit Journal

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.