My mother walked Liido Beach every morning when pregnant.I know the mineral scent of saltwater wherever I am.If the sun bakes the metal of earth, if my own damp scalp sweats,if I hold my hennaed palms to my face.I have said, “God. There is no god but God” into my metallic palms.When my blood started, war started.Ever since the war started, I dye a henna disk on each palm.I refresh it when it browns, old blood. “God,”into my mineral palms when the whole street was white sheets,thin men digging graves night til dawn til night til dawn.They paused for every single prayer.An orb of light dragged me through a dim street, lifted me off my feet.I shouted, “This is my light!” and held it tight against my belly.I was still, beyond known stillness,a gravity of my own, and still I didn’t light the street.The last thing my mother promised me was a photo of her,five months pregnant, at the shore, backlit by the ocean.“Go at dawn,” she’d say. The water was warmest at dawn.Girls went to the beach in whatever they were wearing,even if they had school later. Their mothers couldn’t keep themfrom the water, from walking fully dressed into it.There was nowhere to go but Liido.The orb, a giant marble in my diaphragm, would float with me there.There was nowhere to go but into the ocean.Between this interior desert and the edgeof my known world, orange pekoe-tinted sandmarked with the heels and balls of firm and dazed feet.Charred acacias facedown in the dust.Succulents marking clusters of graves. Graves of peopleand fruit-bearing trees. Bones of tall livestock,the startling domes of camel ribs lit like a great hallby the relentless sun. There is nowhere to go but the ocean.Between here and its mineral scent, bones of people,small and not small, bush lions and their young,always litters of bones at the line between knownand wild worlds. Between here and Liido, the landin full prostration. The only song, metallic. Shells,or whole bullets underfoot, sometimes whole pilesat the edges and centers of towns put facedownat night, at dawn, during afternoon prayer, at dusk.Between here and Liido, the land and everything in itin full submission to the mineral scent of our waterand blood and inability to cry anything,not even “God! No god but God!” We go at dawn.

Landscape Genocide

Feature Date

- November 20, 2019

Series

- Editor's Choice

Selected By

- Amaud Jamaul Johnson

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

Copyright © 2019 by Ladan Osman

All rights reserved.

An earlier version of “Landscape Genocide” was published

in Callaloo, Volume 39, Number 2, Spring 2016, Johns Hopkins University.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

Joe Penney

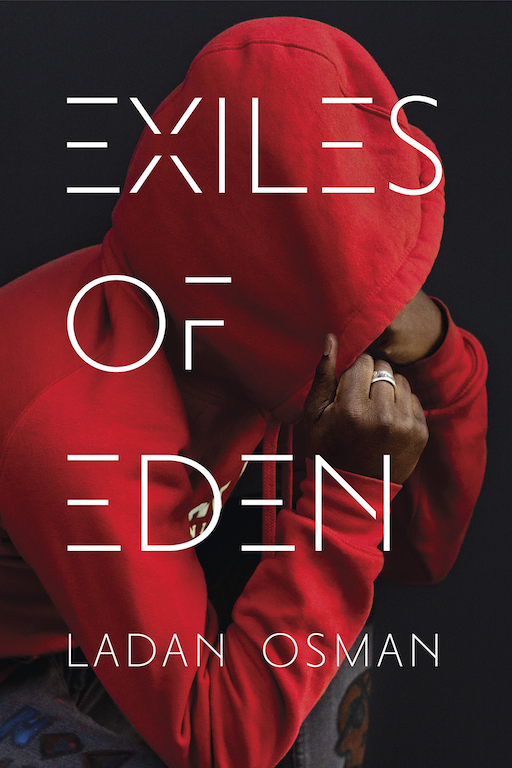

Ladan Osman, Somali-born poet and essayist, is the author of The Kitchen-Dweller’s Testimony (University of Nebraska Press 2015), winner of the Sillerman First Book Prize, and the chapbook Ordinary Heaven, which appeared in the box set Seven New Generation African Poets (Slapering Hol Press 2014).

Poems steeped in the Somali tradition refract the streets of Ferguson, the halls of Guantánamo, and the fields near Abu Ghraib through the myth of Adam and Eve to ask: What does it mean to be a refugee?

“A generous, rooted, and humbly adamant quest for agency.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A stellar collection . . . in this political moment charged with so much frustration and sorrow, Exiles of Eden offers the triumph we all need.”

—World Literature Today

“Ladan Osman is one of the most alive minds in poetry today. Under her supreme gaze, the ordinary is allowed safe passage into strangeness and the surreal is domesticated without losing its innate chaos. Whether with the pen or with the lens, everything is lifted to a higher, fantastic dimension in the frame of Osman’s looking. Exiles of Eden scares me. It’s that good. I didn’t know you could do with language what Osman does, but thank the gods she did.”

—Danez Smith

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.