said the womenfolk where I was raised, and in my mindmercy was a verb, the action reflexive. Though of course the wolf in the kingdom of winter does not mercythe elk. The owl does not mercy the harethat has trembled loose from its delicate coat of stillness. The word has been used since the twelfth century to meanGod’s forgiveness of his creatures’ offenses.Such mercy is not what my father had in mind when he asked me to take a pistol to livein the wilderness. I didn’t. That was nothow I imagined my days, strapping its cold weight to my hip, a saunter to the river: Good morninglarkspur, good morning death camas and moon-flower: I am more deadly than you. Would I slip it into the crook of the quince tree whileI crouched to weed kale? And would I, after all,shoot a bear eclipsing my doorway? Would I shoot a man? Back home, another gunin the safe where my bedroom dresser used to stand.Out there, the news, a loaded gun, returns again and again to the loaded gun. Herethe old growth murmurs at night, the dark’s bonesgroan and creep. Once, barefoot in starlight the color of gingerroot, trembling on the porchat the unknowable’s cacophony, the dog in a huff,I wondered if the fear, in the end, would get me first. On the long, hawk-spangleddrive east, all things appeared to me as bodies: the loghaulers piled with the fallen forms of fir coming down from the mountains, chicken truckswith their live cargoes crushed into hunchbackand the smashed daisies of feathers from which a dim red eye looks out. Across the frostbitflatlands of Idaho, gleaming silver trucks piledwith fleshy potatoes: bodies, bodies, and on the radio a story about a body unearthed from highin the Andes, a woman’s form arrayed with spearand ax-head, a big-game hunter. I want to summon a blessing on this vanishing year—but I forget howthis works, what to say, in what order.I’m thinking of my good Aunt who for all those years and even after the chemo and the electro-shock therapy tucked her pale delicate chin at tableand said with quavering but without irony, We give thanks. The moon’s between the fir’s ribs,up there in the god-dark black. The fox still movesin the roots and the rust. You could say and not lie that this is most of what I long for in the wayof distance and the way of desire: may the fettersfall from all of us this year. May the wild light get way down in our bones. May we without requital,mercy one another with hands like wings, with unarmed hands.

Mercy Me

Feature Date

- September 30, 2022

Series

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

Copyright © 2022 by Corrie Williamson.

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

Corrie Williamson is the author of two collections of poetry, The River Where You Forgot My Name, a finalist for the 2019 Montana Book Award, and Sweet Husk, winner of the 2014 Perugia Press Prize. Her recent work has appeared in The Kenyon Review, Ecotone, Copper Nickel, The Southern Review, and Pleiades. She lives in Lewistown, Montana, where she is at work on her third manuscript, Your Mother’s Bear Gun.

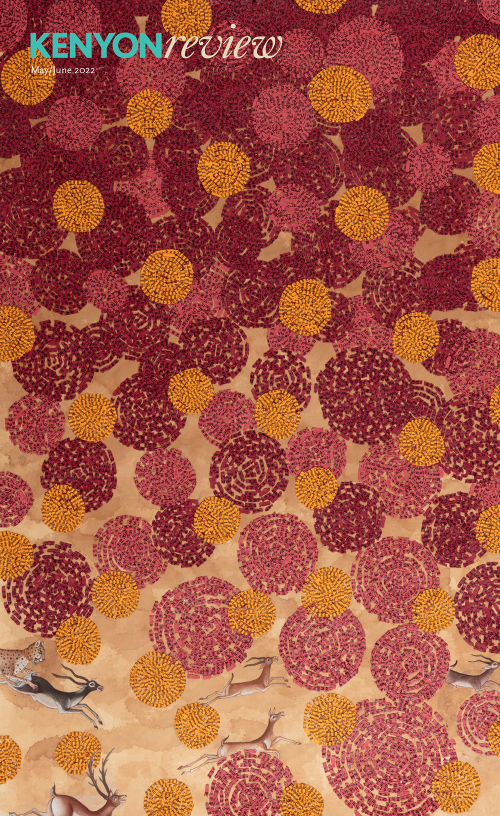

May/June 2022

Gambier, Ohio

Kenyon College

The David F. Banks Editor

Nicole Terez Dutton

Managing Editor

Abigail Wadsworth Serfass

Associate Editor

Sergei Lobanov-Rostovsky

Poetry Editor

David Baker

Building on a tradition of excellence dating back to 1939, the Kenyon Review has evolved from a distinguished literary magazine to a pre-eminent arts organization. Today, KR is devoted to nurturing, publishing, and celebrating the best in contemporary writing. We’re expanding the community of diverse readers and writers, across the globe, at every stage of their lives.

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.