I’m crashing in my parents’ basement tonightbecause it’s closer to my gym, and in the final daysbefore my final fight, even driving home takes too much energy.My father, who at seventy is stillfighting off old age with sweat and suffering,has waited up for me. He’s convincedI face death in the cage to an extent that I unlikely do.Sit down, he says. He’s always hated poetry, yethe wants to read his father’s favorite poem to me.The wind is blowing hard against an archer’s bow.It must be fall because the grass is dried outand the eagles have sharp eyes.Snow begins to drift and the horsestravel quickly. He pauses and looks back.

My Father Reads Wang Wei

Jenny Liou

Feature Date

- December 24, 2022

Series

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

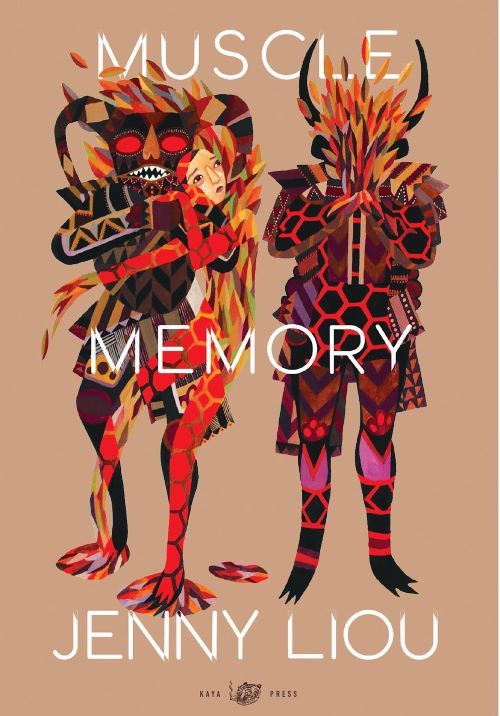

“My Father Reads Wang Wei” from MUSCLE MEMORY: by Jenny Liou.

Published by Kaya Press in October 2022.

Copyright © 2022 by Jenny Liou.

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

Jenny Liou is an English professor at Pierce College and a retired professional cage fighter. She holds a PhD in the History/Rhetoric/Literature of Early Modern Science, an MA in British Literature, an MFA in creative writing, and a BS in biology from the University of California, Irvine, and she was a recent Northwest Climate Adaptation Science Center Fellow at the University of Washington. She lives and writes in Tacoma, WA.

Jenny Liou’s debut poetry collection conjoins the world of cage fighting and the traumas of immigration.

In Muscle Memory, Washington-based poet Jenny Liou grapples with violence and identity, beginning with the chain-link enclosure of the prizefighter’s cage and radiating outward into the diasporic sweep of Chinese American history. Liou writes with spare, stunning lyricism about how cage fighting offered relief from the trauma inflicted by diaspora’s vanishing ghosts; how, in the cage, an elbow splits an eyebrow, or an armbar snaps a limb, and, even when you lose a fight, you’ve won something: pain. Liou places the physical manifestation of violence in her sport alongside the deeper traumas of immigration and her own complicated search for identity, exploring what she inherited from her Chinese immigrant father―who was also obsessed with poetry and martial arts. When she finally steps away from the cage to raise children of her own, Liou begins to question how violence and history pass from one generation to the next, and whether healing is possible without forgetting.

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.