4. At Chief Minster Hun’s Residence On Hearing A Song Resembling “White Linen” 渾鴻臚宅聞歌效白紵A breathtaking beauty parts kingfisher curtainsin the light of a fall moon a dragon blade is unsheathedcrimson lips whisper without making a soundgold pipes and jade chimes echo from the palaceinciting the sky to lower the autumn heatturning the sun to crystal in a world without boundsand these goblets of wine, again, why are we drinking翠帷雙卷出傾城,龍劍破匣霜月明。朱脣掩抑悄無聲,金簧玉磬宮中生。下沉秋火激太清,天高地迥凝日晶。羽觴蕩漾何事傾。33. River Snow 江雪A thousand mountains and not a bird flyingten thousand paths and not a single footprintan old man in his raincoat in a solitary boatfishes alone in the freezing river snow千山鳥飛絕,萬逕人蹤滅。孤舟簑笠翁,獨釣寒江雪。

Two Poems

Liu Tsung-Yuan

Translated from the Chinese by Red Pine

Translator’s Note

Note on 4: This fancy poem depicts the highlights of an evening at the minister’s residence and was written in Ch’ang-an sometime before Liu’s exile in the ninth month of 805. Hun Chien was the minister in charge of vassal state ceremonials. An odd number of lines was unusual in Chinese poetry, but Liu is emulating the seven-line song “White Linen” in which the rhyme is carried by the second, fourth, sixth, and seventh lines. The second line here refers to a sword dance, and the pipes in the fourth line were made of metal and consisted of half a dozen or more vertical tubes. Clearly, by the time he was thirty, Liu’s skill as a poet transcended the versification common among court officials. Unfortunately, we have only these four examples of his early work. (1250)

Note on 33: Written in Yungchou in the winter of 807. The Yungchou region experienced a rare and an unusually heavy snowfall that year. Until modern times, the most common foul-weather gear in China for those who worked out of doors was made from the bark of palm trees. This is Liu’s most famous poem. It’s become a staple of painters. (1221)

Feature Date

- November 14, 2019

Series

- Translation

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

Copyright © 2019 Translation by Red Pine

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

After a failed push for political reform, the T’ang era’s greatest prose-writer, Liu Tsung-yuan, was exiled to the southern reaches of China. Thousands of miles from home and freed from the strictures of court bureaucracy, he turned his gaze inward and chronicled his estrangement in poems. Liu’s fame as a prose writer, however, overshadowed his accomplishment as a poet. Three hundred years after Liu died, the poet Su Tung-p’o ranked him as one of the greatest poets of the T’ang, along with Tu Fu, Li Pai, and Wei Ying-wu. And yet Liu is unknown in the West, with fewer than a dozen poems published in English translation.

Bill Porter assumes the pen name Red Pine for his translation work. He was born in Los Angeles in 1943, grew up in the Idaho Panhandle, served a tour of duty in the US Army, graduated from the University of California with a degree in anthropology, and attended graduate school at Columbia University. Uninspired by the prospect of an academic career, he dropped out of Columbia and moved to a Buddhist monastery in Taiwan. After four years with the monks and nuns, he struck out on his own and eventually found work at English-language radio stations in Taiwan and Hong Kong, where he interviewed local dignitaries and produced more than a thousand programs about his travels in China. His translations have been honored with a number of awards, including two NEA translation fellowships, a PEN translation award, the inaugural Asian Literature Award of the American Literary Translators Association, a Guggenheim Fellowship, which he received to support work on a book based on a pilgrimage to the graves and homes of China’s greatest poets of the past, which was published under the title Finding Them Gone in January of 2016, and more recently in 2018 the Thornton Wilder Prize for Translation bestowed by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He lives in Port Townsend, Washington.

Port Townsend, Washington

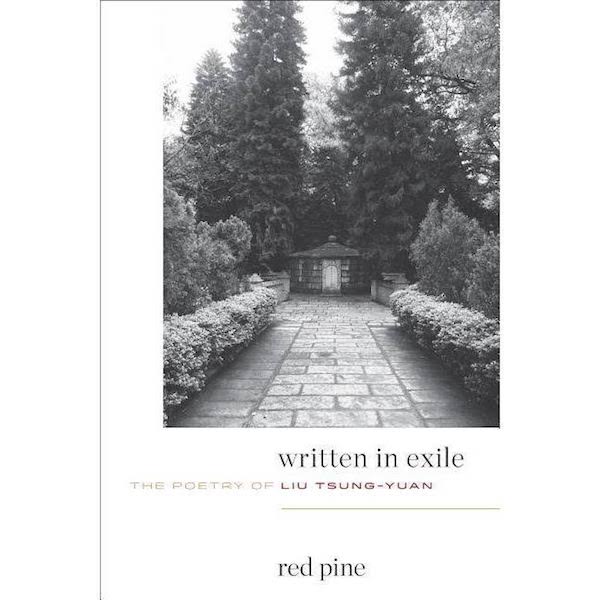

The renowned translator Red Pine discovered Liu’s poetry during his travels throughout China and was compelled to translate 140 of the 146 poems attributed to Liu. As Red Pine writes, “I was captivated by the man and by how he came to write what he did.” Appended with thoroughly researched notes, an in-depth introduction, and the Chinese originals, Written in Exile presents the long-overdue introduction of a legendary T’ang poet.

"This bilingual collection provides readers with generous, thoughtful contextualizing material and a memorable introduction to Liu’s vivid writing."

—Publishers Weekly

“A lifetime devoted to understanding Chinese culture and spirituality blossoms within its pages to create something truly rare.”

—Los Angeles Review of Books

“This book is handsomely produced, brilliantly and usefully annotated, and filled with lines that achieve a casual and compressed balance.”

—Los Angeles Times

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.