1.Each year when winter came, the old men enteredthe woods to gather the moss that grewon the north side of certain junipers.It was slow work, taking many days, though thesewere short days because the light was waning,and when their packs were full, painfullythey made their way home, moss being heavy to carry.The wives fermented these mosses, a time-consuming projectespecially for people so oldthey had been born in another century.But they had patience, these elderly men and women,such as you and I can hardly imagine,and when the moss was cured, it was with wild mustards and sturdy herbspacked between the halves of ciabattine, and weighted like pan bagnat,after which the thing was done: an “invigorating winter sandwich”it was called, but no one saidit was good to eat; it was what you atewhen there was nothing else, like matzoh in the desert, whichour parents called the bread of affliction— Some yearsan old man would not return from the woods, and then his wife would needa new life, as a nurse’s helper, or to supervisethe young people who did the heavy work, or to sellthe sandwiches in the open market as the snow fell, wrappedin wax paper— The book containsonly recipes for winter, when life is hard. In spring,anyone can make a fine meal. 2.Of the moss, the prettiest was savedfor bonsai, for whicha small room had been designated,though few of us had the gift,and even then a long apprenticeshipwas necessary, the rules being complicated.A bright light shone on the specimen being pruned,never into animal shapes, which were frowned on,only into those shapesnatural to the species— Those of us who watchedsometimes chose the container, in my casea porcelain bowl, given me by my grandmother.The wind grew harsher around us.Under the bright light, my friendwho was shaping the tree set down her shears.The tree seemed beautiful to me,not finished perhaps, still it was beautiful, the mossdraped around its roots— I was notpermitted to prune it but I held the bowl in my hands,a pine blowing in high windlike man in the universe. 3.As I said, the work was hard—not simply caring for the little treesbut caring for ourselves as well,feeding ourselves, cleaning the public rooms—But the trees were everything.And how sad we were when one died,and they do die, despite having beenremoved from nature; all things die eventually.I minded most with the ones who lost their leaves,which would pile up on the moss and stones—The trees were miniature, as I have said,but there is no such thing as death in miniature.Shadows passing over snow,steps approaching and going away.The dead leaves lay on the stones;there was no wind to lift them. 4.It was as dark as it would ever bebut then I knew to expect this,the month being December, the month of darkness.It was early morning. I was walkingfrom my room to the arboretum; for obvious reasons,we were encouraged never to be alone,but exceptions were made—I could seethe arboretum glowing across the snow;the trees had been hung with tiny lights,I remember thinking how they must bevisible from far away, not that we went, mainly,far away—Everything was still.In the kitchen, sandwiches were being wrapped for market.My friend used to do this work.Huli songli, our instructor called her,giver of care. I rememberwatching her: inside the door,procedures written on a card in Chinese characterstranslated as the same things in the same order,and underneath: We have deprived them of their origins,they have come to need us now.

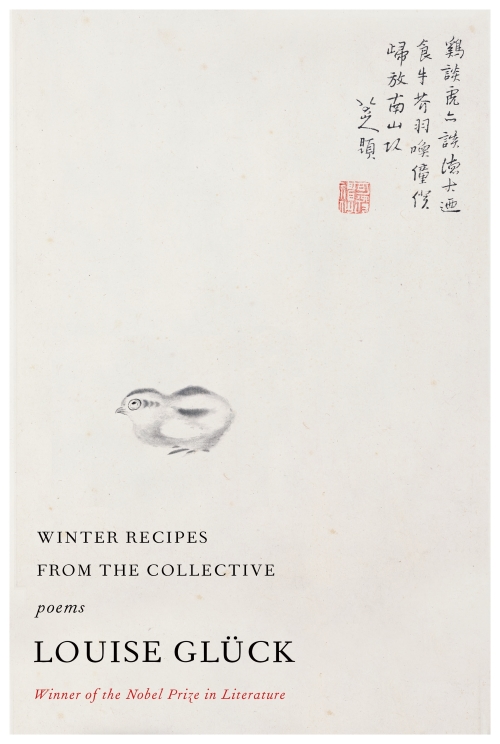

Winter Recipes from the Collective

Feature Date

- November 20, 2021

Series

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

“Winter Recipes from the Collective” from WINTER RECIPES FROM THE COLLECTIVE: by Louise Glück.

Published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux October 26th, 2021.

Copyright © 2021 by Louise Glück.

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

Katherine Wolkoff

Louise Glück is the author of two collections of essays and more than a dozen books of poems. Her many awards include the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature, the 2015 National Humanities Medal, the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for The Wild Iris, the 2014 National Book Award for Faithful and Virtuous Night, the 1985 National Book Critics Circle Award for The Triumph of Achilles, the 2001 Bollingen Prize, the 2012 Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Poems 1962–2012, and the 2008 Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets. She teaches at Yale University and Stanford University and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

"[Winter Recipes from the Collective] is refreshing in its willingness to confront the uncertainties and anxieties ignited by our current predicament, in which predictions of our collective future alternate between the terrifying and the inscrutable . . . Reading Glück’s new poems is a joyful experience, as reading great poetry always is."

—Troy Jollimore, The Washington Post

"[Glück is] a fastidiously exact truth-teller; her lucid poems pretend to a plainness that’s really the simplicity of something more fully worked out than the rest of us can manage . . . [Winter Recipes from the Collective] examines close relationships without the sweetener of correct sentiment, recording the universal stages of human life through a woman’s experience. We’re back in the stylised, half-dreamed Glück landscapes that are rural equivalents of an Edward Hopper painting, and back with her astonishing poetry, as the world goes by, / All the worlds, each more beautiful than the last."

—Fiona Sampson, The Guardian (UK)

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.